Contributed by award-winning author, Ed Lin

Contributed by award-winning author, Ed Lin

[Note: Ed Lin generously conducted a writing workshop that would help launch our community Anthology book project. Thank you, Ed!]

I am willing to tell you about my writing process in the form of snippets if you promise me that you won’t adopt any of it wholesale. What works for me probably won’t for you, although I hope you find elements that are useful.

I can reduce my method to three phrases: 1) no rituals; 2) follow your distractions fully; and 3) let your kids play.

Well, when I was trying to seriously write my first book, I had set up all these rules for getting in the “writing zone.” I had to have a certain CD on, a certain snack at the ready and a two-bottle liter of Coke with a certain cup to drink it from.

I think I coped with that for a few months when I realized that I had set up a ritual for my writing. Some nights I would pass on writing because, oops, there were no more chocolate-coated Digestive cookies. No Coke in the house? Guess I can’t write.

Having a ritual wasn’t helping me to prep to write. It was an excuse *not* to write.

I ended up scrapping everything. No more excuses. I drank water and I wrote.

It’s hard for me to have a regular writing schedule because all too often, I don’t feel like writing when the free time I’ve set aside arrives.

I am not a masochist. I will not chain myself to the computer in order to punch out a preset minimum of words. I will not live that stereotype of the writer going to a cafe…only to log in to social media or write emails.

If you’re going to procrastinate, why do it in a half-assed sort of way? Go to the movie theater. Watch two films. Take yourself out for a full meal. Get ice cream after. See concerts.

I believe that the impulse to procrastinate comes from the creative process. That process can’t be completed if you keep forcing your brain back to the keyboard. Don’t be that parent trying to drag their kid back into the house. Let your kid run loose. Indulge your imagination.

What always happens — for me, anyway — is that I’ll be lost in a film and then realize something about what I am writing, what the next step should be or how to fix an element that wasn’t working. I’m newly motivated and I can’t get to my keyboard fast enough.

One of my favorite writers, Charles Willeford, believed in the art of apparently doing nothing in order to further his writing. I’m not going to put it in quotes because I don’t remember the exact wording, but he said something along the lines of: You’re really writing but your wife just sees you sitting there, drinking a beer.

The last thing I’ll say about my writing process in this space is that I never work on just one story or book. I always have at least two active files I work on. I am easily bored and nothing can do it like working on just one thing. I started what became my second book, This Is a Bust, even before I was done with my first, Waylaid. The latter had a first-person voice that was so, um, extroverted and driven, it left a vacuum in my mind that I had to fill with the extremely withdrawn and marginalized character of Robert Chow in Bust. Working on one primed me to work on the other.

I used to only write two books at the same time but lately, it’s been one book and a series of short stories on the side. Or short stories and a book on the side.

I became a father almost four years ago and since then I’ve been writing short stories and giving them boys’ names. I’m not sure why I’m writing short stories because I haven’t written many before. I don’t tell my kids how to play, I just let them.

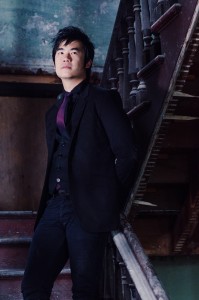

Ed Lin, a native New Yorker of Taiwanese and Chinese descent, is the first author to win three Asian American Literary Awards and is an all-around standup kinda guy. His latest book, Incensed, a Taipei-based mystery, was published by Soho Crime in October.

Support your independent bookstore by purchasing it here!

Here is a listing of Ed Lin’s books.

Bio: Ed Lin, a native New Yorker of Taiwanese and Chinese descent, is the first author to win three Asian American Literary Awards and is an all-around standup kinda guy. His latest book,

Bio: Ed Lin, a native New Yorker of Taiwanese and Chinese descent, is the first author to win three Asian American Literary Awards and is an all-around standup kinda guy. His latest book,

Through the Internet and TV, we are constantly being bombarded with stories that other people want us to take for our own. It is sometimes easy to forget our own stories and who we truly are.

Through the Internet and TV, we are constantly being bombarded with stories that other people want us to take for our own. It is sometimes easy to forget our own stories and who we truly are. There are a handful of Asian storytellers who perform nationally at large storytelling festivals and it is rare for any two of us to perform at the same festival at the same time. I tell stories from Asia, Hawaii, and from the Asian American Experience so that audiences may glimpse other cultures and hear other perspectives. It is an obligation, a duty, and a privilege.

There are a handful of Asian storytellers who perform nationally at large storytelling festivals and it is rare for any two of us to perform at the same festival at the same time. I tell stories from Asia, Hawaii, and from the Asian American Experience so that audiences may glimpse other cultures and hear other perspectives. It is an obligation, a duty, and a privilege. Family stories are particularly precious and easy to preserve. Turn on the video recorder on your cell phone, ask the elders in your family what it was like when they were growing up and record them telling their stories. They are a part of your story. You may not be interested in their stories, but your children or your children’s children might. When the old ones go, they take their stories with them.

Family stories are particularly precious and easy to preserve. Turn on the video recorder on your cell phone, ask the elders in your family what it was like when they were growing up and record them telling their stories. They are a part of your story. You may not be interested in their stories, but your children or your children’s children might. When the old ones go, they take their stories with them. Author Bio: Storyteller Alton Takiyama-Chung grew up with the stories, superstitions, and the magic of the Hawaiian Islands. This gives him a unique perspective to tell Asian folktales and ancient Hawaiian legends, historic stories of WWII Japanese Americans and the Hawaiian Monarchy, and personal Asian American stories. He was awarded the National Storytelling Network’s first J.J. Reneaux Emerging Artist Award in 2005. He has performed at the Bay Area Storytelling Festival, the Cayman Islands Gimme Story Storytelling Festival, Singapore’s Congress of Asian Storytellers, the Asian American Storytelling Festival, as the Teller-in-Residence at the International Storytelling Center, and as a New Voice Teller and Emcee at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, TN. He is also the former Chairman of the Board of Directors of the National Storytelling Network. He can be contacted at

Author Bio: Storyteller Alton Takiyama-Chung grew up with the stories, superstitions, and the magic of the Hawaiian Islands. This gives him a unique perspective to tell Asian folktales and ancient Hawaiian legends, historic stories of WWII Japanese Americans and the Hawaiian Monarchy, and personal Asian American stories. He was awarded the National Storytelling Network’s first J.J. Reneaux Emerging Artist Award in 2005. He has performed at the Bay Area Storytelling Festival, the Cayman Islands Gimme Story Storytelling Festival, Singapore’s Congress of Asian Storytellers, the Asian American Storytelling Festival, as the Teller-in-Residence at the International Storytelling Center, and as a New Voice Teller and Emcee at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, TN. He is also the former Chairman of the Board of Directors of the National Storytelling Network. He can be contacted at