Contributed by special guest writer, Lauren Yanase

In early June, during protests following the atrocious murder of George Floyd, my Boomer-age Japanese American father expressed frustration about certain happenings in the news. He reiterated his general support for the demonstrations, then paused before saying, “You know, those people are horribly racist to us too.”

In early June, during protests following the atrocious murder of George Floyd, my Boomer-age Japanese American father expressed frustration about certain happenings in the news. He reiterated his general support for the demonstrations, then paused before saying, “You know, those people are horribly racist to us too.”

‘Those people’ were understood to be Black Americans, while ‘us’ was Asian immigrants and their Asian American children.

When pressed for his reasoning, he replied, “You know, they hate us ‘model minorities.’ They ‘ching-chonged’ me as much as any White kid growing up in the Sixties.”

Therein lies the answer to my unasked question: what formative encounter had he experienced to codify such views? How could my progressive, sensitive father believe that the long history of violent racism inflicted by White people on Black people is comparable to conflict between BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) communities?

Of course, this was not my first or only experience with casual anti-Black sentiment in my Asian American family and community.

As a Japanese American, family is everything – and nothing is more important than the sacred act of being together. My father’s extended family, numbering over fifty people, has come together for each holiday, big or small, for the past half-century. The most significant loss during the Coronavirus pandemic has been the inability to celebrate together; to break bread together; to simply be together.

Like many American families, ideologies within my dad’s family range from deeply conservative to extremely liberal and everything in between. And, like many families, there are strong opinions and emotions that vary wildly on race issues in America. It was counter-intuitive to me that anyone who had been discriminated against on the basis of race could be Anti-Black. How could those who lived through one of the worst violations of Asian American human and civil rights (the Japanese American incarceration camps) believe the worst of a group whose existence is a continued testament to their push for acceptance in a nation they helped build?

Like many American families, ideologies within my dad’s family range from deeply conservative to extremely liberal and everything in between. And, like many families, there are strong opinions and emotions that vary wildly on race issues in America. It was counter-intuitive to me that anyone who had been discriminated against on the basis of race could be Anti-Black. How could those who lived through one of the worst violations of Asian American human and civil rights (the Japanese American incarceration camps) believe the worst of a group whose existence is a continued testament to their push for acceptance in a nation they helped build?

Ironically, there are deep, old roots of Anti-Black sentiment in my dad’s non-White family that lead to an attitude remarkably similar to the unforgiving racism carried by my mom’s White, old-genteel-Southern family.

Like most American families, my father and I come from a legacy of immigrants. His grandparents came from Japan in the late 19th century. The early history of Asian immigrants on the West Coast is notably marked by the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad and the subsequent Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But my great-grandparents held tight to their American Dream even though their new home was actively hostile against them.

Because of their radical pilgrimage and establishment, my father’s late grandparents are revered legends in my family and their American legacy weighs on our shoulders decades after their passing. An underappreciated fact of my family’s patriarch and matriarch was their unswayable, documentable anti-Black ideology in a time when they, too, were the targets of gross racial discrimination. My father grew up hearing his grandparents using English and Japanese slurs against Black people and their perceived offenses against our family. His father, my late grandfather, a state prosecutor, was convinced that Black people were intellectually inferior.

Anti-Blackness is embedded in my Japanese family’s roots, immigration story, and consequently our political identity. The racial obstacle my family faces now is acknowledging and confronting the anti-Black sentiment that has persisted for over a century in our heritage and our identity. Whenever this is mentioned in my family, I hear the uncomfortable “they were a product of their time” explanations … and more. Their intent is clear: don’t dishonor your great-grandparents’ memory by asking about their shortcomings.

It can be hard, then, to feel empowered to confront my family members’ views since setting aside individuality for the sake of deference to elders is doctrinal.

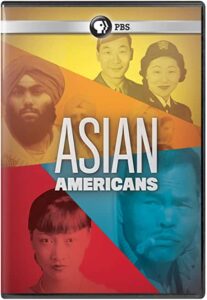

About a month prior to the killing of George Floyd, PBS released a fabulous five-hour film series, “Asian Americans,” on the history of Asian Americans starting from the first migrants. Particularly galling to me was a historian’s tongue-in-cheek summation of the plight of non-European immigrants and migrants: “each immigrant group is striving to be as far from ‘Black’ as possible.” In a gross generalization of the immigrant experience, this quip reveals the fundamental foundation behind assimilation culture: the systemic, institutionalized racism Black people face in America is so pervasive around the world that non-Black immigrants and Americans must distance themselves as far from Blackness as possible.

About a month prior to the killing of George Floyd, PBS released a fabulous five-hour film series, “Asian Americans,” on the history of Asian Americans starting from the first migrants. Particularly galling to me was a historian’s tongue-in-cheek summation of the plight of non-European immigrants and migrants: “each immigrant group is striving to be as far from ‘Black’ as possible.” In a gross generalization of the immigrant experience, this quip reveals the fundamental foundation behind assimilation culture: the systemic, institutionalized racism Black people face in America is so pervasive around the world that non-Black immigrants and Americans must distance themselves as far from Blackness as possible.

As a non-Black person, qualifying Blackness is impossible and inappropriate, so I will not attempt to try. I will say, however, that the non-Black perception of Blackness is often derived from stereotypes and pop culture. The tropes we consume from those media inform the unwritten non-Black POC (People of Color) handbook on achieving acceptance and admittance to White America.

And so is the paradox of Blackness for non-Black POC; we must shun and distance ourselves from the most egregiously ‘Black’ behaviors up until the point they are co-opted by White American pop culture.

With the quiet time that quarantine has afforded me, I realized that there is nothing more reverential to my family’s legacy than using the voice given to me.

The lived history of Asian Americans is radical: existing, struggling, learning to thrive in a space that has tried to exclude them from the beginning. In that way, Asian America is more similar than it is different from Black America. As a 21st century Asian American, I stand on the shoulders of Black abolitionists, suffragettes, civil rights leaders, and advocates. The object now is to demonstrate these fundamental affinities in our communities and broaden a coalition of support for Black empowerment.

The lived history of Asian Americans is radical: existing, struggling, learning to thrive in a space that has tried to exclude them from the beginning. In that way, Asian America is more similar than it is different from Black America. As a 21st century Asian American, I stand on the shoulders of Black abolitionists, suffragettes, civil rights leaders, and advocates. The object now is to demonstrate these fundamental affinities in our communities and broaden a coalition of support for Black empowerment.

I am not the first nor the last of my background to opine on and decry the apparent disconnect of my community to the plight of Black people in America and the bastardization of ‘Blackness.’ From outrage over skin-lightening creams to collaboration in the Civil Rights movement there is a through-line in history, however narrow, of Asian Americans as allies to Black lives. Unfortunately, as a whole, Asian Americans have not tied our empowerment to a synchronous Black liberation.

As poor White Southerners were intentionally turned against their Black peers in the Reconstruction Period and beyond, Asian Americans have tried to distinguish themselves as far from Blackness as possible. It must be my intention as a fourth-generation Asian American to promote breaking down the systemic walls that isolate minority groups from one another. We must be willing to risk the discomfort and offense of our Asian American families and be advocates because it is incumbent on the partnership of Black and Asian Americans to secure equality and dignity for both.

BIO: Lauren Yanase is a recent graduate of St. Mary’s Academy in Portland, Oregon. An avid storyteller, Lauren has previously written creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of Japanese American internment and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her documentary about the Japanese American internment (see description of Shikata Ga Nai below). This is a prestigious honor, with fewer than six percent of Girl Scouts worldwide earning this award.

BIO: Lauren Yanase is a recent graduate of St. Mary’s Academy in Portland, Oregon. An avid storyteller, Lauren has previously written creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of Japanese American internment and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her documentary about the Japanese American internment (see description of Shikata Ga Nai below). This is a prestigious honor, with fewer than six percent of Girl Scouts worldwide earning this award.

Lauren is attending Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont, following a gap year of working in outdoor education and community organizing. She is an enthusiast of mid-priced coffee and semi-athletic endeavors in the mountains.

Shikata Ga Nai: An Inconvenient American follows the story of the Kato family during World War II as Japanese Americans along the West Coast were being forcefully relocated into incarceration camps. John Golden, a TOSA in Portland Public Schools, says that this film, “sheds a light on a forgotten and shameful chapter in American history… and presents a story that is compelling and should be essential viewing for all high school students.”