This month’s blog contributor is Dmae Roberts who wrote the story, My Brother–The Keeper, in our Anthology, Where Are You From?: An Anthology of Asian American Writing

For years I’ve whimsically called myself “Secret Asian Woman.” White people generally assume I’m white and have turned to me with a “wink-wink, nudge-nudge” look when they’ve made a comment or joke about Asians. Other Asians have expressed astonishment when I’ve revealed my bi-racial identity.

As Secret Asian Woman, my mission has been to call out racism that’s usually directed at other people. I’ve spent my adult years looking for a name to answer the question: what are you? I’ve usually had to check the “other” box when identifying my race. It’s only been in the last decade that there has been a mixed-race, multiracial or bi-racial category.

I was born in Taiwan and lived in Japan until I was eight-years-old. When my family moved to Oregon, we lived pretty much in isolation regarding other APIs. Before social media, mixed-race people couldn’t find each other as easily as we can now. I find hope in all the mixtures of millennial Americans who accept each other’s races without having to define it into a “check other” box. Social media allows people to call out racism more easily and to find community and kinship as multiple races.

In 1989, I came out from “undercover” as a secret Asian when I created my radio documentary Mei Mei, A Daughter’s Song. Since then I’ve written personal radio pieces, stage plays and essays delving into my identity and family history. During the three-year period of my mom’s illness, I started several chapters of a memoir while taking care of her. After she passed away, writing about the grieving process got too painful so I paused for a couple of years. Instead I excerpted short essays from the larger memoir that were published in anthologies, magazines and my Asian Reporter column. One piece was My Brother—The Keeper, which was published in Where Are You From?

I pitched my memoir to agents and publishers at a couple of writing conferences, but they all seemed confused and resistant to my story because it was so intertwined with my family stories. Agents especially would ask, “Is it your story or your mom’s or brother’s story?” And while they responded to my mom’s WWII dramatic story of being sold into servitude in Taiwan when she was a child, they thought my personal story didn’t have the same drama. It didn’t seem enough to write an honest exploration into identity and family history.

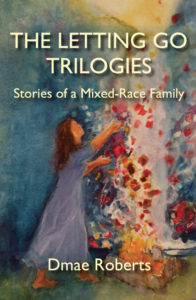

So last year I received a grant from the Regional Arts and Culture Council to hire editors and formatters to independently publish The Letting Go Trilogies: Stories of a Mixed-Race Family. The stories are sets of three essays that were written over a decade about mixed-race identity and my family’s experiences. I also include the stories I wrote when my mom was ill. It’s all about letting go of the pain, grief, anger and regret I’ve experienced in Oregon. It’s also about forgiving one’s self in order to move forward and heal. My book has become a way to start conversation about what it’s like to be mixed-race in a mostly white area. It’s empowering for me, and, I believe, for people who read it.

All my life I’ve had difficult conversations with people about race when I lived in Eugene and then Portland. In the next year, I’ll be having new kinds of conversations as part of the Oregon Humanities Conversation Project. My topic is entitled: What Are You? Mixed-Race and Interracial Families in Oregon’s Past and Future. I’ll be going to different towns and cities in Oregon, leading conversations about mixed-race. I’m looking forward to having these conversations. Mixed-race is the fastest growing demographic. Finally, more people like me. Perhaps I’ll get to talk with you either at a book reading or a conversation project event. I hope so. Secret Asian Woman is not so secret anymore.

The Letting Go Trilogies is available via CreateSpace. (See also my detailed bio.) It is available in both book and Kindle formats on Amazon. It’s also available directly from me on my website. My other projects are available at MediaRites.