Contributed by special guest writer, Becky Morgan

Nisei Daughter, a library find, appealed to me because I knew what Nisei meant, and as I began the read, I saw that it was a memoir set in Seattle in the 1920s, an area I’m familiar with now, a century later. It also takes place partly in the Midwest, where I’ve also spent a good portion of my life.

Nisei Daughter, a library find, appealed to me because I knew what Nisei meant, and as I began the read, I saw that it was a memoir set in Seattle in the 1920s, an area I’m familiar with now, a century later. It also takes place partly in the Midwest, where I’ve also spent a good portion of my life.

First-generation-born-in-the-U.S. also applies partially to my own children, since my husband and his family moved to the U.S. from an Eastern European country when he was twelve. My own side of the family is a mish-mash of nineteenth century, mostly Northern European immigrants. I never thought any particular group of people had a special right to be considered Americans, including Native Americans, who also immigrated here from somewhere else, probably Siberia, at least in the Northwest.

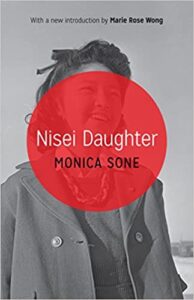

First published in 1952, the book recounts Monica Sone’s life growing up as the daughter of Issei, Japanese American parents both born in Japan, who owned and operated a hotel in the “Skid Road” area of downtown Seattle. Learning, to her surprise, that she was “Japanese” in addition to “Yankee” and would have to go to Japanese school after her American school let out in the afternoon instead of playing with her friends, Monica begins a journey of self-discovery. She attempts to piece together aspects of her personality, cultural and historical background, and life experiences, to form her own identity.

Well-written and expressive, this book shows us a lively young woman who has a warm family life at an interesting and, at times, semi-tragic period in our nation’s history. It contrasts the life of Issei Japanese Americans, born in Japan but developing a different culture in the U.S., with the Nisei, American-born children, Americans not always accepted as American by other U.S. citizens. It also contrasts the Issei and Nisei with their relatives in Japan, during a poignant visit there with Monica’s uncles, aunts, and grandfather: since a U.S. law in 1924 forbade further immigration from Japan, Monica’s father decided they should make the ocean voyage to visit the family there. From Monica’s brother screaming because he doesn’t want to remove his shoes to enter a restaurant, to Monica’s being amazed at her cousin sitting so politely still, while she herself at other times would do ten cartwheels – the contrast between cultural norms is seen, while the family connection remains.

Monica’s family was forcibly moved to the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. They were among the lucky families who were able to keep their business, the hotel, partly because of loyal friends and employees who ran it for them in their absence. Nevertheless, it took a good deal of resilience to cope with the experience of being removed from one’s home and confined to living in one room with furniture Monica’s father built from a pile of scrap lumber. It was especially difficult to endure the indignity of being held without having committed a crime or even being accused of one.

Monica’s family was forcibly moved to the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. They were among the lucky families who were able to keep their business, the hotel, partly because of loyal friends and employees who ran it for them in their absence. Nevertheless, it took a good deal of resilience to cope with the experience of being removed from one’s home and confined to living in one room with furniture Monica’s father built from a pile of scrap lumber. It was especially difficult to endure the indignity of being held without having committed a crime or even being accused of one.

I didn’t know that there were more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent imprisoned behind barbed wire fences, guarded by military police. 77,000 were American citizens (and many more probably would have been citizens if the 1924 law hadn’t removed that possibility). The fact that many Japanese Americans living in Hawaii and German Americans living in the U.S. weren’t incarcerated shows how irrational and particularly unfair the selection of who to imprison was. And it must also have been partly motivated by greed, or why else did many of the prisoners never get their properties back?

Monica was allowed to leave the concentration camp in 1943 for a job in the Midwest, where she later went to college. One thing that surprised me was that Monica felt that she was treated better by the people she got to know in the Midwest than by those she knew in Seattle. In fact, she was appreciated for who she was as an individual and not just as a member of a particular group. This does fit in with current psychological research which shows that we tend to have less prejudiced attitudes towards people we know as individuals than toward groups of people we perceive as “different” and somehow “threatening” to us. This is not a logical thought process but a gut-level reaction that doesn’t go through the thinking parts of our brain.

Overall, Monica’s life was filled with the wonder, fun, and challenges of growing up as well as the difficulties of her own cultural and historical experiences. She found individual people interesting and was a keen observer of personalities, later becoming a clinical psychologist (like the author of this review!).

I suppose if I was going to give this review a bird-watcher’s perspective, I could say that if something is right on top of you, like happening in the moment, you can’t always see it very well. You need the right amount of distance – not too close and not too far – to focus and see what’s there. Memoirs are valuable for many reasons but I’m always glad to read one that describes a life experience that is different from mine. Memoirs help us know people as individuals so that we will be more inclined to see them as fellow humans and not be threatened by them even if they might not look like us.

Becky Morgan is a retired clinical psychologist (and bird watcher) who lives on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington and loves to read. And no, that bird did not actually land on her head – it was photoshopped there by a photographer-neighbor with a sense of humor!

Becky Morgan is a retired clinical psychologist (and bird watcher) who lives on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington and loves to read. And no, that bird did not actually land on her head – it was photoshopped there by a photographer-neighbor with a sense of humor!