Contributed by Anthology author, Simon Tam

Contributed by Anthology author, Simon Tam

It’s Monday morning. June 19, 2017. After working fifteen-hour days everyday for a month straight, I’m bleary with exhaustion. It is one of the few remaining days that the Supreme Court could possibly publish their decision on my case. Fifty-fifty chance it happens this morning.

Oregon Public Broadcasting’s tweet is before my eyes: SCOTUS Rules in Favor of The Slants. I open my email and see my attorney’s one word note with the decision attached. “Congratulations.”

I’m shaking as I open the file, trying to work my way through the dense legal opinion written by Justice Alito. I want to know how the court is divided, what they actually say, how my life’s work is judged by the nation’s highest court. I’m only a few pages in when a ring erupts the silence. It’s a reporter trying to get the scoop. It is only minutes after the high court’s decision. They ask me the obvious question:

“How do you feel?”

I stammer out something that sounds like a canned speech, including being “humbled and thrilled,” though I’m not feeling anything at all. I hang up and text my publicist. Supreme court ruled in our favor. I publish a statement on the Slants’ website and social media. It’s been about thirty minutes since the decision was released and I’m already at about 2,000 messages.

I am setting up interviews every ten minutes for the next ten hours, but most of my calls are interrupted by other reporters who are “breaking” the story. And it does feel broken: I quickly scan the news and see how every major media outlet begins reporting on the issue: “Washington Redskins Win Supreme Court Decision,” “Redskins Score Major Victory in Supreme Court Case,” “Offensive Speech Now OK Says Supreme Court.” I click on the only headline that mentions the band’s name and a photo of the Redskins’ football helmet appears on my screen.

…

For years, I had dreamed of the moment of vindication. I imagined how it would feel to be a part of the legacy of social justice, even if it was only through an obscure part of law. Just a few months earlier, I had a dream where the Supreme Court ruled in our favor. In that scenario, the curiosity about our David vs. Goliath case led people to look at how the law was being applied: inconsistently, subjectively, and improperly. People weren’t talking about football teams; instead, they were finally paying attention to the narrative of the marginalized. Of course, it was only a dream.

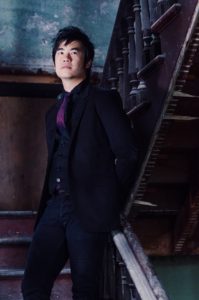

Simon Tam, a member of the band The Slants, speaks to reporters outside the Supreme Court.

The euphoria that I was expecting was instead replaced with dread and disgust. The press had re-framed our struggle and the major concepts about liberty into a narrative around a racist football team. I didn’t feel vindication for our victory; I felt a deep sense of injustice. I felt far more responsibility to provide an answer to the flurry of tweets from a number of Native American activists.

There’s no doubt that these individuals were expressing their dismay at what they perceived as delivering victory on a silver platter to Dan Snyder, owner of the Washington Redskins. And it was me, Simon Tam, who had delivered the head of John the Baptist to Herod Antipas. In a flurry of tweets, I was accused of being a native-born person of color perpetuating the work of colonizers. They characterized this decision on trademark registration law as the floodgate for hate speech. They intimated that I single-handedly doomed all efforts to remove mascots from pro sports.

I tried to address some of the concerns by offering clarity around our process and how trademark laws work. I tried to express how the law I’d been fighting had allowed the government the ability to deny rights based on people’s race, gender, and sexual orientation. I even explained that I’d met with over 140 social justice groups, including numerous confederated tribal leaders. I sincerely wanted to engage with empathy. But my engagement on Twitter only seemed to create greater fury, more harsh personal accusations of bad will and selfish motivations.

I felt frustration, confusion, and sadness.

…

Almost eight years of my life – about 2,800 days – had been poured into this battle for self-identity. And now that it is over, I realize that the fight isn’t really over. I have learned the following lessons:

First, there is a difference between an ethical standard and a legal one. While we’d like to think that what is legal is also right, we know that the enforcement of the law allows more room for the privileged, for dominant groups to abuse laws. In this instance, if we were to give the government power to discern the difference between marginalized identities being re-appropriated and those abusing speech, we are extremely naive in thinking that they have the ability or interest in doing so. They’ve repeatedly failed, which is why the law was used primarily against people of color and the LGBTQ community.

Second, we have to seriously question whether or not the battleground for these kinds of issues should be waged at the desks of examining attorneys at the Trademark Office: does a trademark registration (or lack of) actually address racism? I would say not. And if the law is being used against marginalized communities, that type of institutionalized discrimination creates greater harm than trademark registrations. What the media – and most people – don’t understand is that if the campaign to get the Washington football team’s trademark registration was successful, it still wouldn’t force the team name to change. In fact, it wouldn’t even hurt them because they have so much trademark equity (brand usage, resources), they would still have 100% protection over their trademark. Is symbolic victory that doesn’t actually accomplish the goal of getting the team name to change worth the dehumanizing process of suppressing re-appropriation movements of the marginalized? I would argue that it is not.

We have to think about our end goal of justice: what does it look like? Instead of focusing on punishing the wicked, such as the Washington football team, true equity is creating more options in our society for those who have the fewest. Otherwise, we’re so blinded with the former activity that we are willing to accept the collateral damage being experienced by the marginalized. If the government truly cared about fighting against racism through the Trademark Office, why didn’t they begin by cancelling registrations for the KKK, Stormfront, or other known white supremacist groups? Why did they choose to wage this battle against The Slants, Dykes on Bikes (lesbian motorcycle group), HEEB Media (Jewish magazine), and others engaged in anti-discrimination work? As the marginalized, our biggest struggles are not against harmful language – people will always find ways to abuse and twist words – our biggest challenges are against institutionalized and systemic discrimination, such as outdated processes that do not allow our communities to progress.

Bio: Simon Tam is an author, musician, entrepreneur, and activist. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. His work in the arts has been highlighted in over 3,000 media features across 200 countries including The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, BBC, NPR, TIME Magazine, and Rolling Stone.

Bio: Simon Tam is an author, musician, entrepreneur, and activist. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. His work in the arts has been highlighted in over 3,000 media features across 200 countries including The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, BBC, NPR, TIME Magazine, and Rolling Stone.

He was named a champion of diverse issues by the White House and worked with President Barack Obama’s campaign to fight bullying. He recently helped expand freedom of speech through winning a unanimous victory at the Supreme Court of the United States for a landmark case in constitutional and trademark law (Matal v. Tam).

Simon has been a keynote speaker, performer, and presenter at TEDx, SXSW, Comic-Con, The Department of Defense, Stanford University, and over 1,200 events across North America, Europe, and Asia. He has set a world record by appearing on the TEDx stage 12 times.

He designed one of the first college-accredited social media programs in the United States. Bloomberg Businessweek called him a “Social Media Rockstar.” Forbes says his resume is a “paragon of completeness.”

Recently, he was recognized as a Freedom Fighter by the Roosevelt Rough Writers, named Citizen of the Year from the Chinese American Citizens Alliance Portland Lodge, Portland Rising Star from the Light a Fire Awards, received a Distinguished Alum Award from Marylhurst University, and the Mark T. Banner award from the American Bar Association.

He serves as board chair for the APANO United Communities Fund and member/advisor for multiple nonprofit organizations dedicated to social justice and the arts.

You can find Simon’s appearances, writing, and current projects at www.simontam.org