Contributed by Anthology artist and writer, Roberta May Wong

The day was sunny and bright. I was moving briskly through downtown Portland, Oregon. “GO BACK WHERE YOU CAME FROM!” said a low, gruff voice as I walked past the bus stop next to Portland’s Art Museum. I stopped mid-stride, immobile. Multiple thoughts and emotions dashed through my mind before I spun around and faced the fortyish, disheveled man. I looked him in the eyes and asked, “Are you talking to me?”

He would not look at me. Could only mutter under his breath.

I asked him, “And what ocean did your ancestor cross to be here?”

Mumble mumble was all I heard, followed by more indistinguishable replies.

I told him if he knew his history he would know that we all come from somewhere else, and, by his criteria, only indigenous people really belong in the United States.

This was not yesterday. This was over thirty years ago, in the early ‘80s. But whether then or now, how can anyone have an intelligent conversation when ignorance prevails? To what degree must I consider the mental health, intellect, prejudices or biases that skew the validity of contrary opinions?

One can only know one’s own truth. As a First Generation, American-Born Chinese I know my history. I know who I am. In the ‘60s, Ethnic Studies programs developed in the academic communities of San Francisco State University and the University of California, Berkely. But Asian American Studies had yet to be offered in Oregon when I attended Portland State University in the ‘70s. To learn about the Chinese experience in early America required independent research. By the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Asian-American scholars were producing publications documenting the social and political realities of Chinese immigrants. My growing collection of Asian American books began to fill the void, providing an historical context to my ancestors’ lives. I never asked my parents about their experience as immigrants, and I never met my grandfather who died in 1947. This made me more attentive to family conversations and stories of the past. I came to appreciate and value family connections and collaborations as I witnessed my family’s strong work ethic and honest labor in manifesting their American Dream.

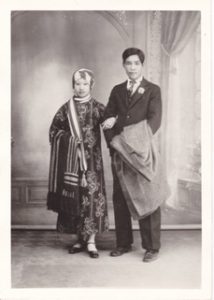

My Parent’s Wedding Day

Mah Yook Fong (Helen Wong) and Wong Gang Foon (Francis Wong)

April 27, 1931

My parents’ immigration stories differ from those of my paternal grandfather, Wong Soon Yook. Between 1882 and 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Acts prohibited or restricted Chinese immigration to America. However, as a merchant, my grandfather was exempted and allowed entry in 1926. By 1930, he established his grocery store, Tuck Lung Company (Prosperity with Integrity) in Portland’s Chinatown and arranged for his two sons to join him. Arriving as teenagers, the sons attended Atkinson Grade School through the fifth grade in NW Portland. They learned their basics: reading, writing and arithmetic. They worked hard, stocking shelves and delivering groceries, and learned to operate the business as they acclimated to a new life. I heard tales of how they carried 50-pound bags of rice up the long flight of stairs to the kitchen of Hung Far Low and how they learned to cook from the chefs at the Republic Café and Hung Far Low. They gained life skills and learned the social norms of Portland’s lively Chinese community, once the second largest on the west coast in the 1900s. The brothers returned to China in 1934 when my grandmother arranged brides for each of her sons. This was a common practice, but their time as newlyweds was limited. They returned to the States without their wives because a 1904 immigration law prohibited merchant wives from entering the U.S. Twelve years would pass before my parents would reunite. As a World War II serviceman, my father became a new citizen, allowing his young family to immigrate after the war. My mother had given birth to twins in China, so she arrived at Angel Island with her sons. In 1947, they each became Resident Aliens with “green cards.”

My Grandfather and his Children:

Right to left: my mother, my father (#2 son), #2 Aunt, #1 Aunt with daughter, #3 Uncle, Grandfather, #1 Uncle and his wife

My grandfather, a resident of the American Hotel on NW 2nd & Flanders, had already settled my uncle with his family in 1941. My father’s family followed six years later, settling in a second floor apartment above them. Within the year, my grandfather passed away, my uncle and his family moved to North Dakota, and my parents bought a house in Southeast Portland. By this time, many Chinese were allowed to purchase property and live beyond Chinatown. Southeast Portland was home to many immigrant families, veterans with new wives from European and Asian nations, as well as returning Japanese Issei, Nisei, and Sansei families who had been victims of the WW II Japanese Incarceration. Chinese families with similar immigration paths as my family’s and many African American families completed our neighborhood.

My parents grew their family, adding five girls in order to have one more boy. Decades later I learned that our elder twin, at age four, had died in China of pneumonia. His papers had been given to another village boy to become a “paper son.” My “paper brother,” a veteran of the Korean War and later a career postal worker, eventually disclosed and corrected his status so he could sponsor his own mother and brother to America. My “blood” brother, upon finishing high school, enrolled in college. When charged tuition as a foreign student, he quickly realized he needed to change his status and took his citizenship test. Two years into his studies, his path took a detour. He quit school to help run the grocery store while our father recuperated from an injury. In time he took over the business, moving it to a larger space down the street, adding a café for our father to manage, and with my mother and siblings’ participation, the family business became central to our lives. Everyday after school we would take the Rose City bus (now Tri-Met) into Chinatown.

In the ‘60s, diversity was not commonly used to reference the racial composition of a community, but our SE Portland neighborhood was considerably diverse for that time, and Asian students were well represented. However, being one of four persons of color in my fifth-grade classroom did not shield me from racism. My first experience of an overt racist attack was while playing a map game. Standing before the class with my opponent, our teacher called out the names of cities around the world and the first to point out its location on the map was the winner. My opponent lost and exclaimed: “CHINK!” My teacher, Mr. Howard, was visibly angry and quick to react, removing the boy from the classroom while classmates gasped at the offense. I stood silent at the blackboard. Even at that young age, I knew I was not at fault for his ignorance.

Roberta May Wong is a conceptual/installation artist from Portland, Oregon. Recent exhibitions include: Friends of Lin Bo, a Three-Person Exhibit at Artist Repertory Theatre (2017); We the People, Group show at Blackfish Gallery (2017) and I-Ching Revolution: 101, an Installation at Indivisible (2016). Past exhibitions: Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center, Portland, OR; The Wing Luke Asian Museum’s touring exhibition “Beyond Talk: Redrawing Race” at The Wing Luke Asian Museum, South Seattle Community College of Art and Phinney Center Art Gallery (2005), Seattle, WA; Evergreen State College, WA; Portland Community College, Sylvania Campus, Portland, OR; Autzen Gallery, Portland State University, Portland, OR; New Zone Gallery, Eugene, OR; Hillsboro Cultural Center, Hillsboro, OR; and NW Artists’ Workshop, Portland, Oregon.

Roberta May Wong is a conceptual/installation artist from Portland, Oregon. Recent exhibitions include: Friends of Lin Bo, a Three-Person Exhibit at Artist Repertory Theatre (2017); We the People, Group show at Blackfish Gallery (2017) and I-Ching Revolution: 101, an Installation at Indivisible (2016). Past exhibitions: Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center, Portland, OR; The Wing Luke Asian Museum’s touring exhibition “Beyond Talk: Redrawing Race” at The Wing Luke Asian Museum, South Seattle Community College of Art and Phinney Center Art Gallery (2005), Seattle, WA; Evergreen State College, WA; Portland Community College, Sylvania Campus, Portland, OR; Autzen Gallery, Portland State University, Portland, OR; New Zone Gallery, Eugene, OR; Hillsboro Cultural Center, Hillsboro, OR; and NW Artists’ Workshop, Portland, Oregon.

Wong’s artwork is published in Where Are You From? An Anthology of Asian American Writing, Thymos, Portland, OR, 2012; Myth and Ideology Study Guide: Surviving Myths, Deakin University, Australia, 1990 & 2000 and The Forbidden Stitch: An Anthology of Asian American Women Artists, published by Calyx, Corvallis, Oregon (American Book Award, 1990).

A native of Portland, Oregon, Wong was Gallery Director at the Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center (1985-1988 and 1995-2004), a multicultural, multidisciplinary, nonprofit art organization in Portland, OR. Independently and professionally, Wong promoted, exhibited and advocated for the visibility and economic opportunity of ethnic and cultural artists. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sculpture from Portland State University, 1983.