Contributed by special guest author, Anne Hawkins

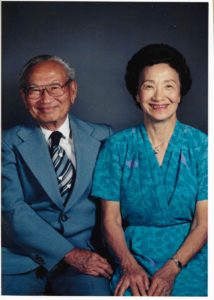

Anne’s grandparents: Takeo & Haruko Fuji

Growing up, I spent my summers with my grandparents. Most afternoons, after lunch, my grandfather took a break from his gardening to watch the Atlanta Braves play baseball on television. He would get up from the couch when the National Anthem played, and he watched the game with a can of Pepsi in hand. From Hawaii, my grandfather didn’t have a local team to cheer for, and it only made sense to him that he should root for the players who had been nicknamed, “America’s Team.” It made sense to me too. After all, everything about my grandfather was just so “American.” He drove a Buick. He watched John Wayne movies. He even claimed his favorite dessert was apple pie. And yet, I know that if my grandfather, the son of Japanese immigrants, walked down the street in almost any city in the United States, people would wonder where he was from. And if he’d said, “America,” they would have responded, “No, but where are you really from?”

I grew up feeling angry, both at this knowledge and because my grandfather himself seemed to harbor no animosity about the situation. After everything that had happened to Japanese-Americans during World War II, I felt like his behavior made him an apologist for our government. But, whenever I told him that eating apple pie wasn’t going to save him, he simply reminded me that he ate apple pie because he loved it.

When I was in high school, Kristi Yamaguchi won the gold medal in figure skating. I had no interest in figure skating, but seeing her photograph on magazine covers mattered. After all, there was nothing more American than winning an Olympic gold medal. Then one day while at a friend’s house, I spied one of those magazines on a coffee table. Another classmate looked over and wondered aloud, “Why would they put her on the cover?” I exclaimed, “Because she won the gold medal!” My classmate responded, “But why do they care if someone who isn’t from the US team wins a gold medal?” I realized that it never occurred to her that someone who looked like Kristi Yamaguchi could actually be an American. Recent comments about Asian-American athletes during the Sochi Winter Games revealed the same prejudice — over two decades later. These incidents served to reinforce the point I’d been trying to make to my grandfather; it doesn’t matter how truly American you are, if you look a certain way, you’ll never belong.

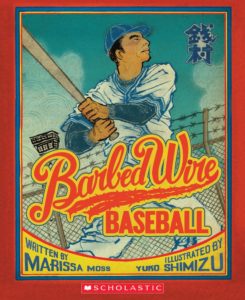

This past week, I read the book Barbed Wire Baseball by Marissa Moss to my seven-year-old son and five-year-old daughters, all of whom have recently become very interested in America’s Pastime. Barbed Wire Baseball tells the story of Kenichi “Zeni” Zenmura, a Japanese-American baseball player. Zeni played baseball in the Fresno Nisei League and the Fresno Twilight League. He played exhibition games alongside Babe Ruth. But none of this saved him from being interned at Gila River in Arizona during the war. The desolate conditions of the prison camp made Zeni feel, “as if he were shrinking into a tiny hard ball.” In an effort to make the camp feel more like home, Zeni took on the arduous task of building a baseball field. He organized daily games, bringing happiness and hope to people whose lives had otherwise been turned upside down.

This past week, I read the book Barbed Wire Baseball by Marissa Moss to my seven-year-old son and five-year-old daughters, all of whom have recently become very interested in America’s Pastime. Barbed Wire Baseball tells the story of Kenichi “Zeni” Zenmura, a Japanese-American baseball player. Zeni played baseball in the Fresno Nisei League and the Fresno Twilight League. He played exhibition games alongside Babe Ruth. But none of this saved him from being interned at Gila River in Arizona during the war. The desolate conditions of the prison camp made Zeni feel, “as if he were shrinking into a tiny hard ball.” In an effort to make the camp feel more like home, Zeni took on the arduous task of building a baseball field. He organized daily games, bringing happiness and hope to people whose lives had otherwise been turned upside down.

This book sparked great conversations between me and my children about the camps — why people were sent to them, what people lost by going to them, and why in the face of issues as serious as racism it might be important to hold onto the love of a game. We talked about how angry people in the camps must have felt about the injustices perpetrated upon them and how it would have been very easy to allow that anger to fester. I wondered if Zeni ever hated baseball or felt like it had betrayed him. We marveled at the incredible resilience ordinary people exhibit under extraordinary circumstances.

Like seeing Kristi Yamaguchi’s face on the cover of Time Magazine, Zeni’s story ignited a sense of pride in me. Sports are a metaphor for the human spirit. They’re about triumph over adversity and attaining success based entirely on hard-work and merit. On the field it doesn’t matter what we look like; all that matters is how we play the game. Zeni was only five feet tall, but he built a baseball field in the desert, and he brought hope to thousands of people. At the end of the book, he’s playing in a game at the camp, and the author writes, “He felt ten feet tall, playing the game he loved so much. Nothing would ever make him feel small again.”

Zeni worked hard to build his field, but in the end he played the game because he loved it. As the author wrote, “When Zeni had a ball or bat in his hand he felt like a giant.” When he hit a homerun, “he felt completely free, as airy and light as the ball he had sent flying.” While who we are necessarily includes how others have viewed and treated us, ultimately it is how we view and treat ourselves that matters the most. You have to do what you love in order to save your own spirit. And while there are days that I allow my anger to fester — when I do think that fighting and speaking out are the answer — I know that to survive I also have to do what my grandfather told me to do so many years ago: simply enjoy that piece of apple pie.

Bio: Anne Hawkins is a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco, California. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband and three children. Her happiest childhood memories are of time spent with her grandparents, and her favorite moments now are watching her own children build the same kinds of memories with their grandparents. She is always on the look-out for children’s books featuring Asian-American characters. Recommendations welcome: annehawk@yahoo.com.

Bio: Anne Hawkins is a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco, California. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband and three children. Her happiest childhood memories are of time spent with her grandparents, and her favorite moments now are watching her own children build the same kinds of memories with their grandparents. She is always on the look-out for children’s books featuring Asian-American characters. Recommendations welcome: annehawk@yahoo.com.