Apo Benigno Bicycled to Hawaii in 1946 and Made a Difference

Special Guest Author: Romel Dela Cruz

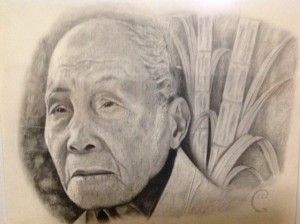

Benigno Apo Tomas Dela Cruz was born in Laoag City, PI. Apo (Filipino/Ilokano word of respect for a venerated elderly person) as he was affectionately called by his apokos (Ilokano word for grandchildren) was a young boy when his father died. He was raised by his mother and siblings. In the 1920s, at the age of 10, his four older brothers emigrated to Hawaii as sakadas (sugar plantation worker recruits from the Philippines). Apo was left behind to farm the small family plot and look after his mother and sister. He did this for almost 30 years and did not appreciate it but had no choice because he was the youngest male with no resources of his own.

Benigno Apo Tomas Dela Cruz was born in Laoag City, PI. Apo (Filipino/Ilokano word of respect for a venerated elderly person) as he was affectionately called by his apokos (Ilokano word for grandchildren) was a young boy when his father died. He was raised by his mother and siblings. In the 1920s, at the age of 10, his four older brothers emigrated to Hawaii as sakadas (sugar plantation worker recruits from the Philippines). Apo was left behind to farm the small family plot and look after his mother and sister. He did this for almost 30 years and did not appreciate it but had no choice because he was the youngest male with no resources of his own.

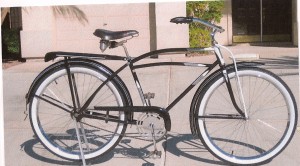

In 1941, at the start of World War II, all of his brothers returned to the Philippines and one gifted Apo with a bicycle. Da bicycle* enabled him to court Asuncion Alonzo to whom he was married for 69 years. During and after the War, the bicycle was Apo’s and Asuncion’s sole means of transportation and the only possession of value that they could truly call their “very own.”

When the War ended in the early months of 1946, Apo heard that the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) was recruiting new sakadas in Vigan, Ilocos Sur, not far from Laoag. He had always been interested in going to Hawaii but was not certain if it was the right time, because the War had just ended and his son was barely a year old. However, Apo’s compadre (godfather of his son), Ricardo, who shared the same apelyido (surname) had completed most of his documents to go to Hawaii but had changed his mind. Apo offered his bicycle to Ricardo in exchange for his documents.

Apo became one of the last surviving 6000 Sakadas transported on the SS Maunawili (an inter-island cattle transport ship) by the sugar and pineapple plantations to work in Hawaii in 1946 to counter the anticipated ILWU strike that would change Hawaii forever.

The HSPA anticipated that the Strike that began on September 1, 1946 would end in their favor just as it always had in the previous fifty years by bringing in new workers (first the Chinese, followed by the Japanese, Portuguese, Europeans and other Caucasians, Puerto Ricans, Koreans and finally Filipinos beginning in 1906) to counterbalance the strikers. But this time, the HSPA had miscalculated.

Apo said that when he and the other Sakadas were on board the SS Maunawili for the 14-day voyage to Honolulu from Vigan, Ilocos Sur, they were secretly educated and advised by the ship’s crew and International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union (ILWU) members of the pending Strike, the concept of pinagmaymaysa (one and united) and the benefits of joining the union for the betterment of all.

At first, Apo was not familiar with all the issues and the struggles of the sugar workers in Hawaii, but he listened and decided to follow despite understanding, too, that it would be a sacrifice because he would not be earning the money he eagerly desired to support himself and his family in the Philippines.

The Strike by the 34,000 sugar plantation workers was supported by the 6000 Sakadas. It lasted for 79 days. Many historians tell us that the Strike of 1946 was important because for the first time, the ILWU-led walk-out was successful in challenging the stranglehold that the sugar and pineapple growers, the Republican Party and other privileged classes had held over every facet of life in the islands for almost 100 years.

The new political and economic influence gained under the leadership of the ILWU and the unwavering support of its members then and in the years that followed transferred political control of governance from the Republicans to the Democrats beginning in 1954. Hawaii went from a territory to a State in 1959. The passage of many progressive laws, some very revolutionary, were instigated to help all workers in Hawaii, not only those in the ILWU. A fair living wage, guaranteed under collective bargaining laws, spawned the growth of a more educated and upward-mobile generation with “roots” tied to the plantations.

Apo, 102 years less 22 days, died at home in Honokaa, HI on October 31, 2015. Employed by Hamakua Mill Co., Paauilo HI, he had been a loyal “rank and file” member of the ILWU for 35 years. He had been a sakada and worked as a cut cane man (sugar cane cutter), sabedong man (herbicide sprayer), tractor operator and truck driver.

Even though Apo contributed to the important events that changed Hawaii, all he really knew was to work hard, provide for his family, and trust his gasat or destiny/luck to take him where he wanted to be. In the beginning, Apo’s bicycle* started off being merely a form of transportation. But that bicycle brought together the lives of two people who then exchanged it to follow their dreams for a better life for themselves and their offspring. Apo’s bicycle* took them from the village of Darayday in the Philippines to Hawaii … and to his part in making better lives for all the workers of Hawaii.

Author Bio: Romel was a plantation boy, born in the Philippines, who came to Hawaii as a young child and grew up in Paauilo, Hawaii. He attended Paauilo School, graduated from Honokaa High School, then went to college in Honolulu, HI and Los Angeles, CA, graduating with a BA in History and a Masters in Public Health from the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Romel volunteered with the US Peace Corps in the Philippines and spent a work career of almost 40 years in education, social and health services of which 25 years was as a hospital administrator, including 12 years at Hale Ho’ola Hamakua (hometown nursing home/critical access hospital), before retiring in 2007. He now tends a little farm in Ahualoa, volunteers in the community, researches and writes about the Filipino experience in Hawaii, and dotes on his three apokos. He is pictured with one of his apokos, Sophia, his 4-year-old granddaughter.

Author Bio: Romel was a plantation boy, born in the Philippines, who came to Hawaii as a young child and grew up in Paauilo, Hawaii. He attended Paauilo School, graduated from Honokaa High School, then went to college in Honolulu, HI and Los Angeles, CA, graduating with a BA in History and a Masters in Public Health from the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Romel volunteered with the US Peace Corps in the Philippines and spent a work career of almost 40 years in education, social and health services of which 25 years was as a hospital administrator, including 12 years at Hale Ho’ola Hamakua (hometown nursing home/critical access hospital), before retiring in 2007. He now tends a little farm in Ahualoa, volunteers in the community, researches and writes about the Filipino experience in Hawaii, and dotes on his three apokos. He is pictured with one of his apokos, Sophia, his 4-year-old granddaughter.

* Photo of a replica of Da Bicycle, based on Apo’s description of it. He indicated that it was Japanese-made and purchased before the start of WWII. During the war when there was a shortage of rubber tires, he shoved rags into the tire which made for a very bumpy ride especially for his wife who rode on the back of the bike, holding onto him, whenever they had to go to town.

* Photo of a replica of Da Bicycle, based on Apo’s description of it. He indicated that it was Japanese-made and purchased before the start of WWII. During the war when there was a shortage of rubber tires, he shoved rags into the tire which made for a very bumpy ride especially for his wife who rode on the back of the bike, holding onto him, whenever they had to go to town.

Sapna Cheryan and Zach Katagiri, two of our Anthology authors, recently published an article in

Sapna Cheryan and Zach Katagiri, two of our Anthology authors, recently published an article in