Contributed by special guest writer, Lindsey Shibata

Contributed by special guest writer, Lindsey Shibata

During the middle of 5th grade, my family picked up everything and moved to Kansas City, Missouri. It’s a place I’ll always remember because it was the first time I ever felt ashamed of being Japanese American.

Within the first week of my new school I was sitting in front of an overly excited ESL teacher who constantly shook with excitement whenever I did something correct. She handed me Kindergarten level storybooks and screeched after I read simple sentences. I was awarded condescending claps and candy; the candy didn’t taste as sweet after being praised for knowing something that I’d known since grade school. I began to believe that there was something wrong with the way I spoke. My self-confidence hit rock bottom, and I managed total silence for the entire week.

I was in constant conflict with myself; I started to blame my culture and ethnicity for my feelings. I started to throw away the “Japanese” part of myself by making sure people only knew the “American” part of me by telling kids I was from California. I believed that because of my Asian roots, people assumed I couldn’t speak proper English.

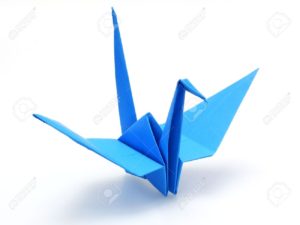

I despised the way I was choosing to live; I hated being known as “the girl who couldn’t talk.” I loathed saying that I was born in California and tossing aside my Japanese culture. I knew I needed to change. Speaking out loud wasn’t an option yet, so I started to think of ways that I could express myself without using words: Japanese Origami. I brought in some origami one day and began to construct different things. As I started to build cranes and irises, people were lighting up with interest. I was spreading this Japanese art form throughout my class, and by the end, they were starting to make things too; I was able to leave them with a little part of my culture in the form of a small iris.

I despised the way I was choosing to live; I hated being known as “the girl who couldn’t talk.” I loathed saying that I was born in California and tossing aside my Japanese culture. I knew I needed to change. Speaking out loud wasn’t an option yet, so I started to think of ways that I could express myself without using words: Japanese Origami. I brought in some origami one day and began to construct different things. As I started to build cranes and irises, people were lighting up with interest. I was spreading this Japanese art form throughout my class, and by the end, they were starting to make things too; I was able to leave them with a little part of my culture in the form of a small iris.

I am a Japanese American, and right now, I embrace this identity. I love being different from everyone else; I enjoy telling people that I was born in Japan. I don’t let this fear and feeling of degradation get in the way of being proud of who I am. Through this experience, I’ve gained self-pride in my identity and continue to cherish my Japanese culture by expressing it without shame. Today, I don’t let anything make me feel ashamed of what it means to be a Japanese American girl.

Bio: Lindsey Hikari Shibata is college student who was born in Okinawa, Japan. Her father is a third-generation Japanese American. Her mother is a native Okinawan. Lindsey moved to the US when she was 2-years-old and has lived in California, in Missouri, and currently resides in Portland, Oregon. She visits Okinawa every other year to maintain ties with her family and relatives, and she has traveled extensively in Japan to continue to learn and experience her native culture.

Bio: Lindsey Hikari Shibata is college student who was born in Okinawa, Japan. Her father is a third-generation Japanese American. Her mother is a native Okinawan. Lindsey moved to the US when she was 2-years-old and has lived in California, in Missouri, and currently resides in Portland, Oregon. She visits Okinawa every other year to maintain ties with her family and relatives, and she has traveled extensively in Japan to continue to learn and experience her native culture.

Artist bio: Ellie is in the sixth grade and likes to read books, even at midnight. Her hobbies include sampling new foods, four square (the recess game), playing devil’s advocate, and thinking up dilemmas. She dreams of peace, fun, a stressless life, and rainbow hair.

Artist bio: Ellie is in the sixth grade and likes to read books, even at midnight. Her hobbies include sampling new foods, four square (the recess game), playing devil’s advocate, and thinking up dilemmas. She dreams of peace, fun, a stressless life, and rainbow hair. This complicated question is explored with thoughtful grace in

This complicated question is explored with thoughtful grace in  The character development is given just the right amount of detail to make us care about Kubo’s journey. The cold stone masks and bone-chilling voices of Kubo’s aunts as well as the utter lack of humanity of Kubo’s grandfather make them memorable antagonists.

The character development is given just the right amount of detail to make us care about Kubo’s journey. The cold stone masks and bone-chilling voices of Kubo’s aunts as well as the utter lack of humanity of Kubo’s grandfather make them memorable antagonists. Fast forward twelve years later to the birth of my first child. It’s a girl, and I have given her my grandmother’s Japanese name. I lay my new daughter down in our living room for the first time and am so struck with the feeling that she has the same serenity as my late grandmother that I have to take a picture of her.

Fast forward twelve years later to the birth of my first child. It’s a girl, and I have given her my grandmother’s Japanese name. I lay my new daughter down in our living room for the first time and am so struck with the feeling that she has the same serenity as my late grandmother that I have to take a picture of her.

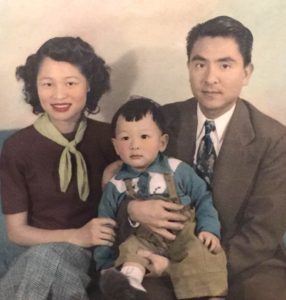

Here I am with my parents.

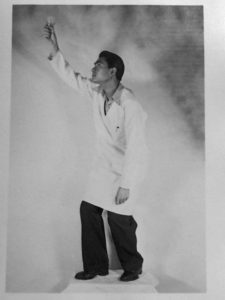

Here I am with my parents. Dad was a great patriot. He went to the war due to the draft but he could have just as easily gone back to China. The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place. He jokingly said, “It’s just my luck, they bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7 and by January 21, I was in the Army!” Like a lot of Chinese men of his generation, being in America was extremely important not only for their own futures but for their families living in China. They were transplants, but they were willing to fight to earn their right to stay. So I chuckle when I see this picture of Dad posing as the Statue of Liberty because I know it was no joke to him. Like the old cigarette ads for Tareyton, he’d rather fight than switch.

Dad was a great patriot. He went to the war due to the draft but he could have just as easily gone back to China. The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place. He jokingly said, “It’s just my luck, they bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7 and by January 21, I was in the Army!” Like a lot of Chinese men of his generation, being in America was extremely important not only for their own futures but for their families living in China. They were transplants, but they were willing to fight to earn their right to stay. So I chuckle when I see this picture of Dad posing as the Statue of Liberty because I know it was no joke to him. Like the old cigarette ads for Tareyton, he’d rather fight than switch. This a picture of my mom working at the Moreland Presbyterian Church cafeteria where The Loaves and Fishes program feeds seniors. They serve food to shut-ins, too; meals are delivered by Meals on Wheels’ volunteers. When my mom worked there in the kitchen, she and supervisor Thelma Skelton received a citation for having one of the most efficient Loaves and Fishes kitchens in the whole U.S.! Less wasted food and good use of resources. They sent an observer to see what they did differently from other kitchens. They found my mom chopping up the leftovers to make hearty soups which were favorites of the large group of seniors that ate there. Mom hates to throw good food out. Way to go Mom and Thelma. When the Loaves and Fishes program moved to its new kitchen at the Sacred Heart Retirement complex at SE Milwaukie Ave and Center St., it was named after Thelma Skelton. She had run the non-profit for most of the years it was at the Presbyterian Church and my mom worked part-time with one other server for most of the years at the new kitchen, too. They were a good team.

This a picture of my mom working at the Moreland Presbyterian Church cafeteria where The Loaves and Fishes program feeds seniors. They serve food to shut-ins, too; meals are delivered by Meals on Wheels’ volunteers. When my mom worked there in the kitchen, she and supervisor Thelma Skelton received a citation for having one of the most efficient Loaves and Fishes kitchens in the whole U.S.! Less wasted food and good use of resources. They sent an observer to see what they did differently from other kitchens. They found my mom chopping up the leftovers to make hearty soups which were favorites of the large group of seniors that ate there. Mom hates to throw good food out. Way to go Mom and Thelma. When the Loaves and Fishes program moved to its new kitchen at the Sacred Heart Retirement complex at SE Milwaukie Ave and Center St., it was named after Thelma Skelton. She had run the non-profit for most of the years it was at the Presbyterian Church and my mom worked part-time with one other server for most of the years at the new kitchen, too. They were a good team. Pictures of my mom through the years. This black-and-white picture of my mom is when she was back in China as a 17- or 18-year-old. She was dubbed “The Atomic Bride” by her friends. She was considered to be more modern than others in their village. My dad met my mom due to the War Brides Act of 1946, which allowed American GIs to go to a foreign country and bring home a wife without having to go through normal immigration procedures and detainment. He had gone to China to see his family and to do what people in his generation did – “go bride shopping” – in the villages adjacent to his own. All of the mothers would bring their unwed daughters to the Dim Sum house in hopes of meeting a husband. My dad told me my mother was taller than average for that part of China. 5’4″ where the average was 5’1″ judging by the height of a lot of her friends and relatives. Most of the population was malnourished in southern China due to the drought and war with Japan. My mom told me people were eating wild grass roots and if it hadn’t been for the bamboo blooming, many people would have died. Bamboo blooms every 25-40 years. My cousins who had lived through the communist take-over and stayed in China until the 1980’s, told me that they only ate twice a day. When I went to China in 1985, I was much taller than the average 20-year-old male. The tallest guys I saw in Guang Dong were 6 feet. Thirty years later, I revisited the city and noticed the height of people had increased 2 to 3 inches! I was still taller but not so much as before. That area of China was eating three meals a day. I had good nutrition and never missed a meal until I went to college.

Pictures of my mom through the years. This black-and-white picture of my mom is when she was back in China as a 17- or 18-year-old. She was dubbed “The Atomic Bride” by her friends. She was considered to be more modern than others in their village. My dad met my mom due to the War Brides Act of 1946, which allowed American GIs to go to a foreign country and bring home a wife without having to go through normal immigration procedures and detainment. He had gone to China to see his family and to do what people in his generation did – “go bride shopping” – in the villages adjacent to his own. All of the mothers would bring their unwed daughters to the Dim Sum house in hopes of meeting a husband. My dad told me my mother was taller than average for that part of China. 5’4″ where the average was 5’1″ judging by the height of a lot of her friends and relatives. Most of the population was malnourished in southern China due to the drought and war with Japan. My mom told me people were eating wild grass roots and if it hadn’t been for the bamboo blooming, many people would have died. Bamboo blooms every 25-40 years. My cousins who had lived through the communist take-over and stayed in China until the 1980’s, told me that they only ate twice a day. When I went to China in 1985, I was much taller than the average 20-year-old male. The tallest guys I saw in Guang Dong were 6 feet. Thirty years later, I revisited the city and noticed the height of people had increased 2 to 3 inches! I was still taller but not so much as before. That area of China was eating three meals a day. I had good nutrition and never missed a meal until I went to college. This color photo of my mom was taken last year. We think she’s 88 or 89. Not sure how accurate her birth certificate is. I did a rough calculation, and she has cooked me 14,304 meals!! And still counting, because for the past 45 years, she is still cooking for me once a week! Love ya Mom!

This color photo of my mom was taken last year. We think she’s 88 or 89. Not sure how accurate her birth certificate is. I did a rough calculation, and she has cooked me 14,304 meals!! And still counting, because for the past 45 years, she is still cooking for me once a week! Love ya Mom! Bio: Dan Chinn was born to Suey Q. and Faye K. Chinn, Portland, Oregon. He graduated from Benson Polytechnic High School (Pre-Engineering, Electronics) and attended PCC and PSU (Electronic Engineering, Poetry, Film Making, and Marketing). He worked at Bell Telephone, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s Portland Branch, Tektronix Inc., and Intel Corporation before retiring in 1998. Dan is now a writer, poet, photographer, artist, and musician.

Bio: Dan Chinn was born to Suey Q. and Faye K. Chinn, Portland, Oregon. He graduated from Benson Polytechnic High School (Pre-Engineering, Electronics) and attended PCC and PSU (Electronic Engineering, Poetry, Film Making, and Marketing). He worked at Bell Telephone, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s Portland Branch, Tektronix Inc., and Intel Corporation before retiring in 1998. Dan is now a writer, poet, photographer, artist, and musician. Contributed by special guest author, Adrianne Kwak

Contributed by special guest author, Adrianne Kwak In any case, watching

In any case, watching  Hearing my grandma singing a seasonally appropriate song was both a gift and a sign for me. Likewise, watching

Hearing my grandma singing a seasonally appropriate song was both a gift and a sign for me. Likewise, watching

Written by Special Contributor, Artist Mark Matsuno

Written by Special Contributor, Artist Mark Matsuno