Thoughts from Award-Winning Filmmaker, Myles Matsuno

Thoughts from Award-Winning Filmmaker, Myles Matsuno

Those who know me will tell you that family is everything to me.

Growing up, it felt like my dad always had a Hi-8 mini DV camcorder ready to roll on my sister and me. The footage was your typical family montage. Us playing sports, opening Christmas presents, school activities, vacation trips, singing 90’s hit songs — the list goes on.

In the 90’s, it took intention and effort to capture these moments. There were no cell phones to point and shoot high quality video. You had to carry around a bulky camcorder in a bag, hoping you had charged the battery, and capture it all on a 60-90 minute tape. And God forbid if you accidentally re-recorded over your little sister’s birthday from the year before …

Back then, that camcorder was just a cool toy to make home movies. Today, the memories captured by that same camcorder are more than just a “no big deal”. They’re everything to me.

It’s part of the reason I’m making films today. It’s the main reason behind what I look for when making a movie: capturing moments. And it plays a big role in why I made my documentary First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family.

The Japanese Incarceration is something that’s glossed over in American history. It was brushed over in my high school and college educations. For some, it wasn’t taught at all. And I get it … it’s embarrassing. America didn’t save the day on this one. In fact, they dropped the ball. But you know what? So did I.

The Japanese Incarceration is something that’s glossed over in American history. It was brushed over in my high school and college educations. For some, it wasn’t taught at all. And I get it … it’s embarrassing. America didn’t save the day on this one. In fact, they dropped the ball. But you know what? So did I.

For someone who cherishes family and stories as much as me, you would’ve thought I’d have taken the time to learn about the subject a little more. I guess that’s what they call being young and naive. But I’ll call it for what it was … being a selfish teenager.

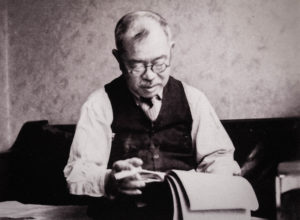

I never took the time to really dig into what my grandparents and roughly 120,000 other Japanese Americans and immigrants went through in this country. It wasn’t until I was in my early twenties that I actually took the time to read the front page of the San Francisco Examiner that my father has framed and hanging on his wall. It’s the same enlarged one-sheet he’s had hanging on his wall for decades. The paper was published on December 8th 1941, and the title reads, “First S.F. Japanese Prisoner.” It has the picture of a Japanese man being handcuffed and escorted out of a hotel by the FBI. That prisoner was my great-grandfather, Ichiro Kataoka, and that hotel was his hotel. I learned that my family legacy is one that is touching, inspiring, and hopeful.

I never took the time to really dig into what my grandparents and roughly 120,000 other Japanese Americans and immigrants went through in this country. It wasn’t until I was in my early twenties that I actually took the time to read the front page of the San Francisco Examiner that my father has framed and hanging on his wall. It’s the same enlarged one-sheet he’s had hanging on his wall for decades. The paper was published on December 8th 1941, and the title reads, “First S.F. Japanese Prisoner.” It has the picture of a Japanese man being handcuffed and escorted out of a hotel by the FBI. That prisoner was my great-grandfather, Ichiro Kataoka, and that hotel was his hotel. I learned that my family legacy is one that is touching, inspiring, and hopeful.

For years, this story resonated within me. I wanted to know everything about it. I would talk to my grandmother about what she went through. I would go to museum exhibits on the subject, read books, and Google whatever I could find online. I even filed for all the documents that were collected on Ichiro Kataoka during that time. And just like my father did with my sister and me, I wanted to document everything. I wanted something tangible. Something I could show my family for generations to come. So, without a real plan, I set out to do just that. Make a film based on my family’s experience of the Japanese Incarceration. And this process has forever changed my life.

For years, this story resonated within me. I wanted to know everything about it. I would talk to my grandmother about what she went through. I would go to museum exhibits on the subject, read books, and Google whatever I could find online. I even filed for all the documents that were collected on Ichiro Kataoka during that time. And just like my father did with my sister and me, I wanted to document everything. I wanted something tangible. Something I could show my family for generations to come. So, without a real plan, I set out to do just that. Make a film based on my family’s experience of the Japanese Incarceration. And this process has forever changed my life.

I get asked quite often how and why I made this film. Questions like… is it for a political agenda? Where did I gather all the footage? What was my intention behind the film? Did it leave me in a vulnerable state putting my family out there for people to see? What’s next now that it’s done?

First and foremost, I made this film for my family. I wanted to preserve our family’s history for current and future generations, so both my family and others will never forget what happened to real people in a time of war. Almost all of the footage in the film is personal. I digitized and captured four different generations dating all the way back to my great-grandfather. Releasing our family’s film to the public as a documentary does make us vulnerable, especially in an industry where critics can be harsh and rejection is common. Sometimes, I didn’t want to let the public see what happened to our family because this would open us up to the judgment of complete strangers. Would I do justice to my family’s story? Make my family proud?

First and foremost, I made this film for my family. I wanted to preserve our family’s history for current and future generations, so both my family and others will never forget what happened to real people in a time of war. Almost all of the footage in the film is personal. I digitized and captured four different generations dating all the way back to my great-grandfather. Releasing our family’s film to the public as a documentary does make us vulnerable, especially in an industry where critics can be harsh and rejection is common. Sometimes, I didn’t want to let the public see what happened to our family because this would open us up to the judgment of complete strangers. Would I do justice to my family’s story? Make my family proud?

In the end it was all worth it. The countless hours of footage watched and digitized, all the family documents gathered from the government, the countless photo albums looked through, the sleepless nights and multiple edit revisions, and the self-doubt that looms over every artist taking creative risks.

In the end, I’m glad I did send the film to festivals and show it in classes. It’s been well-received and we racked up some awards along the way. The most recent win was the audience award at the Sidewalk Film Festival in Birmingham, AL. The audience award means the most to me because it’s the people’s award.

My hope for this film is that it not only educates the viewer but also brings them a sense of hope. A hope that good can come from even the darkest of situations. I don’t downplay Executive Order 9066 issued by President Roosevelt. It was a horrible time in our country. It was a time when racism led to fear and fear led to racism. But like my Aunt Toshi says in the film, “Well as bad as camp was, one thing, I met your dad here. … We were in block 11 they were in block 9 … If it wasn’t for camp you kids wouldn’t be here. … that’s the only good thing… .” That’s the message of hope I’m talking about and it’s overwhelming to see people recognize this hope after watching the film.

My hope for this film is that it not only educates the viewer but also brings them a sense of hope. A hope that good can come from even the darkest of situations. I don’t downplay Executive Order 9066 issued by President Roosevelt. It was a horrible time in our country. It was a time when racism led to fear and fear led to racism. But like my Aunt Toshi says in the film, “Well as bad as camp was, one thing, I met your dad here. … We were in block 11 they were in block 9 … If it wasn’t for camp you kids wouldn’t be here. … that’s the only good thing… .” That’s the message of hope I’m talking about and it’s overwhelming to see people recognize this hope after watching the film.

This film is part of the history of why I’m here today. After making this film I can’t stress enough the importance of knowing where you come from. When our camcorders can fit into our pockets, there shouldn’t be any excuse not to make those memories and capture those moments of yourself, family, and friends. Document and pass them down to the generations that follow so they will know those who came before them.

As my grandma says in the legacy letter I found when making the film, “Just like my mother, I, too, have lived a life of shiawase.” Shi-a-wase in Japanese means fortunate or happiness.

As my grandma says in the legacy letter I found when making the film, “Just like my mother, I, too, have lived a life of shiawase.” Shi-a-wase in Japanese means fortunate or happiness.

After everything she’s been through, she still believes she has “lived a life of happiness.” I hope I can say the same in 60 years.

Bio: Born and raised in Los Angeles, CA, Myles Matsuno focuses on developing meaningful stories that convey strong messages through visual aesthetics. For him, everything he creates comes down to two final factors: the Audience and Moments. Having led efforts for ABC LA in the technical direction of shows such as The Academy Awards, Dancing with the Stars, NBA Finals, and more, Matsuno has also gained international recognition for his films because of their honest and inspiring messages. His films have been shown in many festivals and won awards throughout the country. His latest works are the feature, Christmas in July, and the documentary, First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family. His documentary is expected to be released in December 2017. Please check his websites: www.matsunomedia.com and www.firsttogofilm.com. He may also be contacted through Instagram: @myles_matsuno and Twitter: @MylesMatsuno.

Bio: Born and raised in Los Angeles, CA, Myles Matsuno focuses on developing meaningful stories that convey strong messages through visual aesthetics. For him, everything he creates comes down to two final factors: the Audience and Moments. Having led efforts for ABC LA in the technical direction of shows such as The Academy Awards, Dancing with the Stars, NBA Finals, and more, Matsuno has also gained international recognition for his films because of their honest and inspiring messages. His films have been shown in many festivals and won awards throughout the country. His latest works are the feature, Christmas in July, and the documentary, First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family. His documentary is expected to be released in December 2017. Please check his websites: www.matsunomedia.com and www.firsttogofilm.com. He may also be contacted through Instagram: @myles_matsuno and Twitter: @MylesMatsuno.