Contributed by special guest writer, Margie Tang-Oxley, as part of our collaboration with APANO (see organization description at end of this blog)

I am from a small gold-mining town in Northern California called Grass Valley. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are 12,860 residents of Grass Valley; 188 identify as Asian and 11,493 identify as white. My mother and I are two of those 188. We are also two of only three in my family who live in the United States. The year I graduated from high school, there was one other Asian American enrolled in my school of 784 students. I was the only student who was Chinese American. Growing up, I fixated upon these numbers, feeling the pressure of these statistics weighing on me. I would think to myself over and over again, “My actions are responsible for 50% of the Asian American representation here.” I felt that whatever I did would define who Chinese Americans were in this community. These numbers surrounded me like the bars of a cage, a constant reminder of my cultural isolation.

I am from a small gold-mining town in Northern California called Grass Valley. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are 12,860 residents of Grass Valley; 188 identify as Asian and 11,493 identify as white. My mother and I are two of those 188. We are also two of only three in my family who live in the United States. The year I graduated from high school, there was one other Asian American enrolled in my school of 784 students. I was the only student who was Chinese American. Growing up, I fixated upon these numbers, feeling the pressure of these statistics weighing on me. I would think to myself over and over again, “My actions are responsible for 50% of the Asian American representation here.” I felt that whatever I did would define who Chinese Americans were in this community. These numbers surrounded me like the bars of a cage, a constant reminder of my cultural isolation.

When I graduated from high school, I moved to Portland, OR to study history at Reed College, focusing in particular on Chinese American history. I saw this course of study as a way to free myself from the cage I was in. Even if I was the only Chinese person from Grass Valley, CA, the knowledge of those who shared my experience as an American of Chinese heritage would be my key to freedom — freedom from the crushing Otherness I had felt for so long.

However, as I studied, I began to notice in book after book, in article after article, in lecture after lecture, that the name “Grass Valley, CA” appeared. And once I noticed the name, I saw it everywhere. Suddenly I saw Chinese Americans visiting Grass Valley, spending their youth selling cha siu baos in Grass Valley, panning for gold in Grass Valley, running laundries in Grass Valley. And finally, I saw it: There was once a large Chinatown in Grass Valley. A Chinatown so large that in the second half of the 19th century it contained over 3,000 residents. Grass Valley is a historic town, and so the streets and shop fronts look largely the same as they did during the Gold Rush. Thus, the idea that there were once 3,000 Chinese people walking on the streets I had walked, running shops on the sites where I now shopped, left me speechless. I had never seen remnants of a Chinatown growing up, never learned about one in school, never saw mention of it in our local museum. Where was this Chinatown? Where had my people gone?

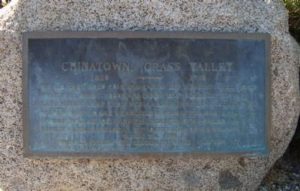

I kept reading and eventually learned that the majority of Chinese residents in Grass Valley had either died, left after economic prospects dried up, or were driven out of town by angry, white mobs. All that was left is a small plaque commemorating the site were this Grass Valley Chinatown had once stood. To this day, I’ve never been able to find that plaque. But now, whenever I go home, I no longer feel so imprisoned by my Chineseness among this white majority. When I walk around, I can feel the spirits of the Chinese Americans who came before me. I can feel the memory of their footsteps on the paths I take. I know that though I never met them, and that I never will, I hold their legacy within me. I carry the torch of the Grass Valley Chinatown that once was. Though in this moment I may be one of only 188 Asian Americans, I am also one of thousands that ever were. And when I remember that, I don’t feel so alone.

I kept reading and eventually learned that the majority of Chinese residents in Grass Valley had either died, left after economic prospects dried up, or were driven out of town by angry, white mobs. All that was left is a small plaque commemorating the site were this Grass Valley Chinatown had once stood. To this day, I’ve never been able to find that plaque. But now, whenever I go home, I no longer feel so imprisoned by my Chineseness among this white majority. When I walk around, I can feel the spirits of the Chinese Americans who came before me. I can feel the memory of their footsteps on the paths I take. I know that though I never met them, and that I never will, I hold their legacy within me. I carry the torch of the Grass Valley Chinatown that once was. Though in this moment I may be one of only 188 Asian Americans, I am also one of thousands that ever were. And when I remember that, I don’t feel so alone.

Bio: Margie was born and raised in Northern California and is a mixed-race second-generation Chinese American. She graduated from Reed College in 2018 with a degree in history. Her senior thesis focused on Chinese American cuisine and how restaurant owners created a sense of authenticity in their establishments during the Cold War. In Fall 2019 Margie will be starting a PhD program in Asian American History. In her free time she enjoys cooking and eating at local restaurants, reading, and spending time with her tiny dog, Chicken Combo.

Bio: Margie was born and raised in Northern California and is a mixed-race second-generation Chinese American. She graduated from Reed College in 2018 with a degree in history. Her senior thesis focused on Chinese American cuisine and how restaurant owners created a sense of authenticity in their establishments during the Cold War. In Fall 2019 Margie will be starting a PhD program in Asian American History. In her free time she enjoys cooking and eating at local restaurants, reading, and spending time with her tiny dog, Chicken Combo.

APANO: Established as a 501c3 nonprofit in 2010, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO) is a statewide, grassroots organization uniting Asians and Pacific Islanders to achieve social justice. We use our collective strengths to advance equity through empowering, organizing and advocating with our communities. APANO’s strategic direction prioritizes four key focus areas: cultural work, leadership development, community organizing, and policy advocacy and civic engagement. Through APANO’s arts and cultural work, we create a vibrant space where artists and communities can envision an equitable world through the tool of creative expression. We strive to impact beliefs, center the voices of those most impacted and silenced, and use arts and cultural work to foster unity and vitality within our communities. Learn more about APANO on our website and read more writings by APANO members on Medium.