Contributed by special guest artist, Roberta May Wong

Artist Roberta Wong (front right) and her siblings. “It took five girls to get one boy.” 1958

I was born the Fifth Chinese Daughter, another parental effort for a First-Born American son. My birth order enabled me to grow up learning how to exist on the fringe – amongst my siblings, within my community, and in American society. Hypocrisy, social injustice and gender bias were some things I was consciously aware of from an early age, but it took decades before I was able and willing to call them out.

My Confucian family life taught me that I was part of a whole, and there was order and purpose to our lives. Each person had value regardless of position, size, role or status. My Taoist perspective put our lives in context with the Universe.

As an artist, I acknowledge that we each are originals – individual beings obligated to be our true selves. We mix and blend materials with concepts to explore and tap our humanity. Our work as social alchemist is in creating intrinsic value within each discovery, either a revelation of self or shared universal truth. Despite social or commercial trends, it is of importance to adhere to one’s vision to find personal truth.

Recently I returned to Chinatown to participate in the second exhibition of the newly-opened Portland Chinatown Museum. Curated by Horatio Law, three Asian American women artists were selected to share their disparate paths and personal connections with Portland’s Chinatown. “Descendent Threads” exhibited Ellen George, Lynn Yarne and myself, Roberta Wong.

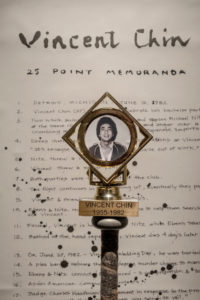

In addition to mutual cultural experiences, Asian Americans have experienced the history of exclusion, racism, violence, murder, social injustice, discrimination, and inequality. Much of my art addresses these social/cultural issues. With titles like Chinks, All-American, All Orientals Look Alike, and Vincent, most of my pieces, accompanied by a written artist statement, are meant to challenge the Asian American narrative. I am hoping that those who experience my pieces will feel a shared visceral response that is both disturbing and self-affirming. Our visibility makes our lives relevant to ourselves and to others.

All-American (detail), Art Installation

Braided hair, Chinese cleaver, round chopping block, stainless steel table, rubber floor mat

42.25” x 36” x 36”

2003

Vincent, Art Installation (Detail)

Vincent, Art Installation

Steel pedestal, plastic tray, toy cars, aluminum baseball bat, plastic/marble trophy, Chinese scroll, brush pen ink.

80” x 15” x 11″

I-Ching Revolution: 101

2 foam core panels, wood, tacks, laminated photos; 64” x 48”

Artist Statement: I-Ching Revolution: 101 visualizes social change and its manifestation through personal courage as represented by small action. When individuals consciously stand with BLACK LIVES MATTERS and “show face” against the injustices confronting our Black communities, lives will change. I invited photo submissions from the community; this simple act of “showing face” symbolizes the courage it takes to face up to social, political, and economic consequences.

Join the revolution, manifest the change.

I was honored to exhibit with two fellow women artists (note: Ellen George and Lynn Yarne will describe their art in Parts 2 and 3 of this 3-part series):

Ellen’s grandmother was born in Portland’s Old Chinatown in the late 1880s. Her grandfather, a young Chinese sojourner, returned to China with his wife where Ellen’s mother was born. In time, her mother came to the U.S. and settled in Texas where Ellen was born. It was only recently that Ellen learned of her grandmother’s connection to and family roots in Portland’s Chinatown. Her art – object-making installations and paintings – are reflective of loving memories of her mother in the comfort of familiar tools: her abacus, her fans, and her language.

Lynn recalls family visits to Chinatown as a child eating at their favorite restaurant. Her two grandmas, although living across the street from one another, recalled different lives – one centered in Chinatown, the other in Portland’s Japantown. Honoring the women in her life, Lynn constructed a community altar, gathering multitudes of photographs to depict a blending of her families, cultures, and histories. These became the basis for her animated video which captured the movements, sounds and stories within an enshrined space.

BIO: Born and raised in Portland, OR, Roberta Wong grew up working behind the counter and in the back kitchen of her family’s grocery and restaurant, Tuck Lung, in Portland’s Chinatown. She attended Portland State University, graduating in Sculpture in 1983. Chinatown was a part of her daily life until 1985 when she entered the nonprofit art sector as a gallery director and art administrator. She spent the next two decades promoting diversity in the arts and creating opportunities for artists-of-color.

BIO: Born and raised in Portland, OR, Roberta Wong grew up working behind the counter and in the back kitchen of her family’s grocery and restaurant, Tuck Lung, in Portland’s Chinatown. She attended Portland State University, graduating in Sculpture in 1983. Chinatown was a part of her daily life until 1985 when she entered the nonprofit art sector as a gallery director and art administrator. She spent the next two decades promoting diversity in the arts and creating opportunities for artists-of-color.

Tuck Lung, hand-carved Philippine Mahogany panel

1976

Recent exhibitions include Portland Chinatown Museum, Artists Repertory Theatre, and Indivisible; past exhibitions: Wing Luke Museum, Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center, Evergreen State College, Portland Community College-Sylvania Campus, Portland State University-Autzen Gallery. Her artwork is published in Where Are You From? An Anthology of Asian American Writing, Thymos, Portland, OR, 2012 (Shelf Unbound award); Myth and Ideology Study Guide: Surviving Myths, Deakin University, Australia, 1990 & 2000 and The Forbidden Stitch: An Anthology of Asian American Women Artists, published by Calyx, Corvallis, Oregon (American Book Award, 1990).