The elation of watching the first Black and Asian American woman sworn in as Vice President soured when, in the face of rising anti-Asian violence, the Biden-Harris Administration failed to install any Cabinet member of AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) descent.

The elation of watching the first Black and Asian American woman sworn in as Vice President soured when, in the face of rising anti-Asian violence, the Biden-Harris Administration failed to install any Cabinet member of AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) descent.

This discrepancy was sharpened in Atlanta, Georgia, where a white man murdered eight people; seven were Asian. Solidarity squares dominated my social media from well-meaning non-AAPI followers. High-profile politicians and celebrities railed against sexual violence against women of (mainly) East Asian descent, bemoaning the “unprecedented” rise in anti-Asian rhetoric. “Stop AAPI Hate,” “Protect Asian Women,” and other low-calorie hashtags flooded Twitter.

Aside from occasional AAPI celebrities and politicians, the anti-AAPI narrative has been drafted mainly by well-meaning persons who don’t claim an AAPI identity. When AAPI people are not leading the movement supposedly for them, the Asian diaspora gets stereotyped as helpless, hapless sex workers or somebody’s auntie or uncle.

To understand why our representation is tied to our civic power, I explored the history of Asian American civic engagement: why is the fastest-growing ethnic group so poorly understood by the non-AAPI public and its representatives? In doing so, I acknowledge my own background as a (Japanese) American and that my own understanding is limited to that experience, too.

The History of Asian American Power

The fractious Asian American community is not a recent development but a product of (predominately White) American public opinion and U.S. immigration legislation. While white Americans inappropriately projected sameness onto migrants from the expansive continent, those arriving instead attached their identities to their homelands.

Notably, waves of anti-Asian sentiment in the United States follow economic trends impacting White Americans. Legislation often reinforced ethnic fault lines: the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (and subsequent Geary Act) embittered Chinese communities against the Japanese migrants who enjoyed the privileges of the Gentlemen’s Agreement into the early 20th century. Subsequently, state legislatures enacted Alien Land laws blocking Asian migrants from owning land. By the late 19th century, Japanese and Chinese immigrants were often at odds from disputes between their homelands and the hostile environment of their new country.

Economic competition between these two largest Asian migrant populations was amplified by racial discrimination. Consternation about Asian immigration engendered the term “Yellow Peril,” and associated violence deepened the division between the communities. The Immigration Act of 1921 effectively barred non-white immigration to the U.S. into the 1960s.

Following the Pearl Harbor bombing, Korean and Chinese Americans distinguished themselves from Japanese peers, wearing buttons announcing their ancestry. During the 1980s, as Japanese auto industries in the U.S. exploded, causing a perceived loss of “American” jobs, Chinese American Vincent Chin was beaten to death, mistaken as being of Japanese descent.

This, limited to East Asian American experiences, is hardly comprehensive but demonstrates the intersectionality of violence against Asians in the United States and the history of pitting one nationality against another to the benefit of neither.

People wait in a line to vote in Queens, N.Y. during early voting for the Presidential election on Oct. 24, 2020.

Modern Political Capital

This history of Asian immigrants trying to differentiate themselves by nationality is perhaps why, despite becoming the United States’ largest immigrant group, with two-thirds of Asians in America being immigrants (Pew Research), collectively, we hold minimal power in public office and the private sector.

Outside the first Asian American woman Vice President, President Biden’s cabinet is infuriatingly devoid of Asian members. As President Biden rewarded former Democratic opponents, he conspicuously overlooked Andrew Yang.

This omission was noticed. The Japanese American Citizens’ League, one of the oldest civil rights groups in the country, condemned this oversight, as did Congress-persons Mark Takano (D-CA) (PBS), and Judy Chu (D-CA) (Vox), and others in the Asian Pacific Islander Caucus. Beyond outrage, however, there is little opportunity beyond calling for more representation.

Which brings me back to my question: Why, in 2021, over a century after the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the Alien Land Laws, are we Asian Americans struggling to gain meaningful traction in the public sphere?

Some might argue that I am focusing on ‘identity politics.’ To that, I say: I am focusing on identity. Because, despite being one of the highest educated and economically successful ethnic groups in the country, we have one of the lowest civic engagement rates by self-identified ethnicity.

Political Divide

Political Divide

Another anomaly of the Asian identity politic is the generalization of voting habits and political identity. While pollsters can partially predict other racial minorities’ collective voting patterns, the same confidence is not afforded to Asian voters. Our voting habits mirror those of white voters, reflecting education and age more than race. This is partially attributable to the diverse Asian diaspora: none of some twenty-five nationalities holds a majority in our ethnic group in America. Subsequently, there are few universal hallmarks of the Asian American experience aside, perhaps, from hate crimes and discrimination.

Without a robust activist body like other racial identities have leveraged for their interests, Asian Americans focus on ethnic identities over our larger demographic. Predictably, this has severe consequences for us collectively and individually. A Washington State school district scrubbed Asian Americans off their list of recognized racial groups, depriving them of civil rights protections (The Ticker). Washington also has consistently voted down Affirmative Action policies to protect Asian American students (NBC News). In 2020, hate crimes against Asians and Asian Americans rose a staggering 150% across the country; several of these incidents have led to serious injury or death. These tragedies are often marked by the media as isolated events, only starting to recognize the causative anti-Asian endemic racism.

Unlike other BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color), Asian Americans often set aside racial identity for other influences. Few of us would say, “As an AAPI, I vote to represent AAPI interests.” Instead, we say, “As a business owner/parent/queer person/religious person/etc., I vote to represent those interests.”

Though President Biden signed an executive order condemning racism against AAPI individuals, his is the first cabinet with no Asian American leading an administrative department. The most partisan Congress in modern history passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act in the same session where President Biden quashed a protest by the only two Asian American Senators for lack of representation by promising to appoint a “Senior Liaison” to the AAPI community.

Conclusion

Conclusion

We are asked to support candidates and parties, and in exchange, are told to be content with what we receive. That exchange is an occasional pat on the head or empty hashtag. The message is clear: the 23 million AAPI Americans are not welcomed at the table we helped set.

As I move into my adult identity, I’ve reckoned with the painful history and current trauma of my Asian heritage contrasting the anemic political force my community holds. Our self-partitioning by ethnic identity was a self-inflicted emasculation; the oppression and violence against our American bodies were not.

In the 21st century landscape of social justice and internet activism, the objective is tangible: making inroads to other cultural communities–not diminishing the experience of either, but coalescing the values of both.

BIO: Lauren Yanase, a lifelong Portland, OR resident, is in her second year at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont.

BIO: Lauren Yanase, a lifelong Portland, OR resident, is in her second year at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont.

An avid storyteller, Lauren has published creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of the Japanese American incarceration and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her documentary about the Japanese American incarceration. This is a prestigious honor, with fewer than six percent of Girl Scouts worldwide earning this award.

Her documentary, Shikata Ga Nai: An Inconvenient American, follows the story of the Kato family during World War II as Japanese Americans along the West Coast were forcefully relocated into concentration camps. John Golden, a TOSA in Portland Public Schools, says that this film, “sheds a light on a forgotten and shameful chapter in American history… and presents a story that is compelling and should be essential viewing for all high school students.” This film and other works can be found at her online portfolio, From Grandma’s House.

When she is not enjoying a mid-priced coffee or semi-athletic endeavors in the mountains, Lauren is studying and working in education and public policy.

Nisei Daughter, a library find, appealed to me because I knew what Nisei meant, and as I began the read, I saw that it was a memoir set in Seattle in the 1920s, an area I’m familiar with now, a century later. It also takes place partly in the Midwest, where I’ve also spent a good portion of my life.

Nisei Daughter, a library find, appealed to me because I knew what Nisei meant, and as I began the read, I saw that it was a memoir set in Seattle in the 1920s, an area I’m familiar with now, a century later. It also takes place partly in the Midwest, where I’ve also spent a good portion of my life. Monica’s family was forcibly moved to the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. They were among the lucky families who were able to keep their business, the hotel, partly because of loyal friends and employees who ran it for them in their absence. Nevertheless, it took a good deal of resilience to cope with the experience of being removed from one’s home and confined to living in one room with furniture Monica’s father built from a pile of scrap lumber. It was especially difficult to endure the indignity of being held without having committed a crime or even being accused of one.

Monica’s family was forcibly moved to the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. They were among the lucky families who were able to keep their business, the hotel, partly because of loyal friends and employees who ran it for them in their absence. Nevertheless, it took a good deal of resilience to cope with the experience of being removed from one’s home and confined to living in one room with furniture Monica’s father built from a pile of scrap lumber. It was especially difficult to endure the indignity of being held without having committed a crime or even being accused of one. Becky Morgan is a retired clinical psychologist (and bird watcher) who lives on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington and loves to read. And no, that bird did not actually land on her head – it was photoshopped there by a photographer-neighbor with a sense of humor!

Becky Morgan is a retired clinical psychologist (and bird watcher) who lives on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington and loves to read. And no, that bird did not actually land on her head – it was photoshopped there by a photographer-neighbor with a sense of humor! For the past four years, we have been led by those who want to build walls. To protect us, they say. To keep them out, they say. But with more and more incidents of “I can’t breathe,” it’s becoming harder to ignore the increasing restlessness born from the suspicion that maybe walls are being built to keep us in. In our places. It’s ironic that the virus we’re dealing with now also makes it difficult for its victims to breathe. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why we can empathize a little more with Eric Garner and George Floyd.

For the past four years, we have been led by those who want to build walls. To protect us, they say. To keep them out, they say. But with more and more incidents of “I can’t breathe,” it’s becoming harder to ignore the increasing restlessness born from the suspicion that maybe walls are being built to keep us in. In our places. It’s ironic that the virus we’re dealing with now also makes it difficult for its victims to breathe. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why we can empathize a little more with Eric Garner and George Floyd. Certainly, the restlessness of 2020 is being caused by lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, working from home, travel restrictions, and other related pandemic measures. More than that, however, is the growing desire to breathe. Take for example our Election. The initial large number of Democratic candidates running for President might have been overwhelming to consider but I was encouraged by its diversity – even an Asian American! Yay Yang! And for the final Democratic candidate to commit to and follow-through with his pledge to pick a woman as his running mate was another surprise. Even though Biden had not been my first choice, his selection of a woman of color made me respect him more.

Certainly, the restlessness of 2020 is being caused by lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, working from home, travel restrictions, and other related pandemic measures. More than that, however, is the growing desire to breathe. Take for example our Election. The initial large number of Democratic candidates running for President might have been overwhelming to consider but I was encouraged by its diversity – even an Asian American! Yay Yang! And for the final Democratic candidate to commit to and follow-through with his pledge to pick a woman as his running mate was another surprise. Even though Biden had not been my first choice, his selection of a woman of color made me respect him more. COVID also showed us that people are not treated equally in America. While our President and the wealthy in our country get the best healthcare, too many Americans don’t. Some die. Too many Americans are losing jobs and homes. They. Can’t. Breathe. Not everyone will recover. Protests happen when groups believe that the balance has shifted from “more to gain” to “less to lose.”

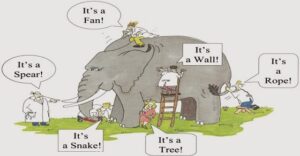

COVID also showed us that people are not treated equally in America. While our President and the wealthy in our country get the best healthcare, too many Americans don’t. Some die. Too many Americans are losing jobs and homes. They. Can’t. Breathe. Not everyone will recover. Protests happen when groups believe that the balance has shifted from “more to gain” to “less to lose.” During this pause, I am having a hard time understanding why others don’t see the hurt and pain – the breathlessness – behind the Protests. Maybe most of us are like those

During this pause, I am having a hard time understanding why others don’t see the hurt and pain – the breathlessness – behind the Protests. Maybe most of us are like those  We don’t live in isolation, we live in families, communities, and societies where our actions can affect others among whom we live as well as those who want to live among us. It may help us breathe more easily and calmly if we tempered our desire for individualism and exclusivity with a more generous caring and kindness to those around us … even when it means acting for the greater good rather than our own preferences. We can choose to build walls … or, as Yo-Yo Ma proposes, bridges:

We don’t live in isolation, we live in families, communities, and societies where our actions can affect others among whom we live as well as those who want to live among us. It may help us breathe more easily and calmly if we tempered our desire for individualism and exclusivity with a more generous caring and kindness to those around us … even when it means acting for the greater good rather than our own preferences. We can choose to build walls … or, as Yo-Yo Ma proposes, bridges: In a better world, we will be able to bridge the divide, tear down walls, problem-solve and accomplish wonderful things together, no matter our race, gender, sexual orientation, age, or political leanings. What we create will be meaningful more than expedient. Built without guns, bombs, tear-gas, batons, and knives. Shaped by kindness and caring for each other no matter how differently we look and think. Listening to each other. REALLY listening. Seeing deeply into each other’s hearts and souls, not just glancing at surfaces and assuming we know. And, in our Election cycles, it would be nice if seeing candidates who look like us was such a normal sight that it wouldn’t make us sit up, breathing accelerated; rather the focus would be on getting very excited about candidates who hope and dream with us no matter what they or we look like.

In a better world, we will be able to bridge the divide, tear down walls, problem-solve and accomplish wonderful things together, no matter our race, gender, sexual orientation, age, or political leanings. What we create will be meaningful more than expedient. Built without guns, bombs, tear-gas, batons, and knives. Shaped by kindness and caring for each other no matter how differently we look and think. Listening to each other. REALLY listening. Seeing deeply into each other’s hearts and souls, not just glancing at surfaces and assuming we know. And, in our Election cycles, it would be nice if seeing candidates who look like us was such a normal sight that it wouldn’t make us sit up, breathing accelerated; rather the focus would be on getting very excited about candidates who hope and dream with us no matter what they or we look like. Bio: Valerie Katagiri was co-editor of the community book project (available on Amazon.com):

Bio: Valerie Katagiri was co-editor of the community book project (available on Amazon.com):  In early June, during protests following the atrocious murder of George Floyd, my Boomer-age Japanese American father expressed frustration about certain happenings in the news. He reiterated his general support for the demonstrations, then paused before saying, “You know, those people are horribly racist to us too.”

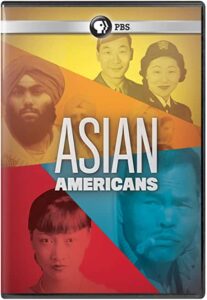

In early June, during protests following the atrocious murder of George Floyd, my Boomer-age Japanese American father expressed frustration about certain happenings in the news. He reiterated his general support for the demonstrations, then paused before saying, “You know, those people are horribly racist to us too.” About a month prior to the killing of George Floyd, PBS released a fabulous five-hour film series,

About a month prior to the killing of George Floyd, PBS released a fabulous five-hour film series,  The lived history of Asian Americans is radical: existing, struggling, learning to thrive in a space that has tried to exclude them from the beginning. In that way, Asian America is more similar than it is different from Black America. As a 21st century Asian American, I stand on the shoulders of Black abolitionists, suffragettes, civil rights leaders, and advocates. The object now is to demonstrate these fundamental affinities in our communities and broaden a coalition of support for Black empowerment.

The lived history of Asian Americans is radical: existing, struggling, learning to thrive in a space that has tried to exclude them from the beginning. In that way, Asian America is more similar than it is different from Black America. As a 21st century Asian American, I stand on the shoulders of Black abolitionists, suffragettes, civil rights leaders, and advocates. The object now is to demonstrate these fundamental affinities in our communities and broaden a coalition of support for Black empowerment. BIO: Lauren Yanase is a recent graduate of St. Mary’s Academy in Portland, Oregon. An avid storyteller, Lauren has previously written creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of Japanese American internment and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her documentary about the Japanese American internment (see description of

BIO: Lauren Yanase is a recent graduate of St. Mary’s Academy in Portland, Oregon. An avid storyteller, Lauren has previously written creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of Japanese American internment and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her documentary about the Japanese American internment (see description of  As we sat in the circle, I asked them to share about a holiday or tradition they celebrate in their family. They spoke about Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Hanukkah – as others in the circle nodded along. And finally, one spoke about a holiday when he dressed in red and ate noodles to represent long life. Where he danced in a line led by a big lion’s head. And when, he smiled, he “gets lots of red envelopes with money.” The others asked questions – they’d heard of this holiday in school and maybe even gone to an event – but they had never listened to someone who celebrated it describe it in such a meaningful way.

As we sat in the circle, I asked them to share about a holiday or tradition they celebrate in their family. They spoke about Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Hanukkah – as others in the circle nodded along. And finally, one spoke about a holiday when he dressed in red and ate noodles to represent long life. Where he danced in a line led by a big lion’s head. And when, he smiled, he “gets lots of red envelopes with money.” The others asked questions – they’d heard of this holiday in school and maybe even gone to an event – but they had never listened to someone who celebrated it describe it in such a meaningful way. Tiffany Jewell’s

Tiffany Jewell’s  BIO: Anne Hawkins is the mother of three elementary-aged children and a criminal defense attorney in the San Francisco Bay Area. When she isn’t leading discussion circles for nine-year-old boys, she can be found reading or pacing on the sidelines of her children’s baseball and soccer games.

BIO: Anne Hawkins is the mother of three elementary-aged children and a criminal defense attorney in the San Francisco Bay Area. When she isn’t leading discussion circles for nine-year-old boys, she can be found reading or pacing on the sidelines of her children’s baseball and soccer games. Recently, I had an impactful (and surprising) discussion around race. Here’s how it went …

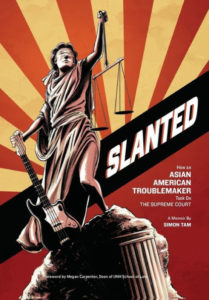

Recently, I had an impactful (and surprising) discussion around race. Here’s how it went … BIO: Simon Tam is an author, musician, activist, and troublemaker. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. He is the founder of The Slants Foundation, an organization dedicated to providing scholarships and mentorship to artist-activists of color.

BIO: Simon Tam is an author, musician, activist, and troublemaker. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. He is the founder of The Slants Foundation, an organization dedicated to providing scholarships and mentorship to artist-activists of color. In 2019, he published his memoir, Slanted: How an Asian American Troublemaker Took on the Supreme Court. You can purchase it wherever books are sold and read excerpts at

In 2019, he published his memoir, Slanted: How an Asian American Troublemaker Took on the Supreme Court. You can purchase it wherever books are sold and read excerpts at  Sending my brother and me to camp was my mother’s idea. She had grand notions about how children should spend their summers to become adults of distinction and believed that summer camp would help us develop American independence. My mother’s desire to send us to camp was also fueled by guilt for having moved our family from Seoul to the United States. We hadn’t been well-to-do in Korea. But we’d definitely been middle-class. My mother had been a middle school teacher, and she and my father had run a cram school out of our house, a spacious home with a yard. In contrast, our home in America was a one-bedroom apartment in Elmhurst, an immigrant enclave in Queens with very little that evoked the pastoral glory that had lured my parents to leave their homeland.

Sending my brother and me to camp was my mother’s idea. She had grand notions about how children should spend their summers to become adults of distinction and believed that summer camp would help us develop American independence. My mother’s desire to send us to camp was also fueled by guilt for having moved our family from Seoul to the United States. We hadn’t been well-to-do in Korea. But we’d definitely been middle-class. My mother had been a middle school teacher, and she and my father had run a cram school out of our house, a spacious home with a yard. In contrast, our home in America was a one-bedroom apartment in Elmhurst, an immigrant enclave in Queens with very little that evoked the pastoral glory that had lured my parents to leave their homeland. I was teased a lot and got called all sorts of names, especially at the start of camp, but overall, I had fun because it was still summer camp and we campers were all little kids. I also won some status at camp for being one of just a handful of kids who could swim and for being the only kid who could do the Rubik’s Cube.

I was teased a lot and got called all sorts of names, especially at the start of camp, but overall, I had fun because it was still summer camp and we campers were all little kids. I also won some status at camp for being one of just a handful of kids who could swim and for being the only kid who could do the Rubik’s Cube. BIO: Yongsoo Park is the

BIO: Yongsoo Park is the  Contributed by special guest author/writer/lecturer, Linda Tamura

Contributed by special guest author/writer/lecturer, Linda Tamura While downsizing and rearranging our home, I’ve taken a second look at remembrances from Mom. And I wonder: How did she balance nine-hour work days hoeing trees or thinning pears with Dad in our orchard or hammering boards into boxes (even with a big bandage from misjudging her finger placement) with cooking, cleaning, doing laundry with a wring-washer and clothes-line while still managing to raise three daughters? And how did she find time to crochet delicate doilies and tablecloths, embroider pillowcases, sew dresses and outfits for all of us – and then find joy in gardening, too? How did she manage to multitask before that concept even became vogue?

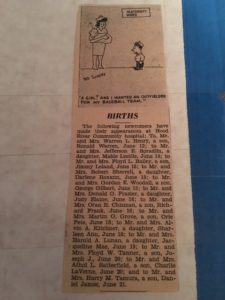

While downsizing and rearranging our home, I’ve taken a second look at remembrances from Mom. And I wonder: How did she balance nine-hour work days hoeing trees or thinning pears with Dad in our orchard or hammering boards into boxes (even with a big bandage from misjudging her finger placement) with cooking, cleaning, doing laundry with a wring-washer and clothes-line while still managing to raise three daughters? And how did she find time to crochet delicate doilies and tablecloths, embroider pillowcases, sew dresses and outfits for all of us – and then find joy in gardening, too? How did she manage to multitask before that concept even became vogue? I recently found the baby book that Mom lovingly compiled 70 years ago. Tucked inside the cover in a plain envelope were two yellowed Hood River News articles. The first, labeled June 18, Parkdale, Oregon, had a simple title: “Baby shower.” It detailed an event hosted by “Miss Jessie Akiyama” three days before I was born. Not only did it list the 17 “mesdames” (listed by their spouses’ names) who attended, but it included the eight who sent gifts but were unable to attend. Notably among the guests were the spouses of two Euro-American men who’d been supportive of my grandparents’ family both before and after the war, despite a caustic community campaign to prevent the return of Japanese Americans after their wartime incarceration. This was a ruthless drive supported by “No Japs Wanted” ads signed by more than 1,800 locals that brought national notoriety to my hometown. So, in a way, after the scourge of wartime exclusion and the fear about how they’d be accepted in their own community, this article represented more than just a celebration of life, albeit mine. It was also an exemplar of friendships and reunions that crossed racist borders, maybe even an oblique call for unity. Could it be that Mom is speaking into my ear again, this time urging our efforts toward the equity and balance that were amiss when she was growing up – and that challenge us in new ways today?

I recently found the baby book that Mom lovingly compiled 70 years ago. Tucked inside the cover in a plain envelope were two yellowed Hood River News articles. The first, labeled June 18, Parkdale, Oregon, had a simple title: “Baby shower.” It detailed an event hosted by “Miss Jessie Akiyama” three days before I was born. Not only did it list the 17 “mesdames” (listed by their spouses’ names) who attended, but it included the eight who sent gifts but were unable to attend. Notably among the guests were the spouses of two Euro-American men who’d been supportive of my grandparents’ family both before and after the war, despite a caustic community campaign to prevent the return of Japanese Americans after their wartime incarceration. This was a ruthless drive supported by “No Japs Wanted” ads signed by more than 1,800 locals that brought national notoriety to my hometown. So, in a way, after the scourge of wartime exclusion and the fear about how they’d be accepted in their own community, this article represented more than just a celebration of life, albeit mine. It was also an exemplar of friendships and reunions that crossed racist borders, maybe even an oblique call for unity. Could it be that Mom is speaking into my ear again, this time urging our efforts toward the equity and balance that were amiss when she was growing up – and that challenge us in new ways today? Oh, and the second article I found? A short clip entitled “Births” listed newborns for the previous week. Mine was the last of thirteen entries, announcing the birth “to Mr. and Mrs. Harry M. Tamura, a son, Daniel James, June 21.” Now my sisters tease me that they had always wanted a big brother …

Oh, and the second article I found? A short clip entitled “Births” listed newborns for the previous week. Mine was the last of thirteen entries, announcing the birth “to Mr. and Mrs. Harry M. Tamura, a son, Daniel James, June 21.” Now my sisters tease me that they had always wanted a big brother … Bio: Linda Tamura is a third-generation Japanese American, an orchard kid raised in Hood River, Oregon and the daughter of a World War II veteran. A Professor Emerita of Education at Willamette University, she is the author of two books on Japanese Americans:

Bio: Linda Tamura is a third-generation Japanese American, an orchard kid raised in Hood River, Oregon and the daughter of a World War II veteran. A Professor Emerita of Education at Willamette University, she is the author of two books on Japanese Americans:  Bio: Summer Tan is a high school sophomore who lives in West Linn. She enjoys mock trial, and her team won first place in the 2020 Oregon State Championship. She loves competing in debate tournaments, participating in Model United Nations, and playing golf with the high school team. She is also currently Vice-Chair of the City of West Linn Youth Advisory Council and has volunteered for various non-profit organizations with the National Charity League.

Bio: Summer Tan is a high school sophomore who lives in West Linn. She enjoys mock trial, and her team won first place in the 2020 Oregon State Championship. She loves competing in debate tournaments, participating in Model United Nations, and playing golf with the high school team. She is also currently Vice-Chair of the City of West Linn Youth Advisory Council and has volunteered for various non-profit organizations with the National Charity League. Portland cellist brings peace during epidemic

Portland cellist brings peace during epidemic

Bio: Michelle Hicks is a Field Organizer at APANO. She was raised in San Jose, CA by her mother, a Korean immigrant, and two incredible older sisters. Her upbringing influenced her to study Politics with minors in American Ethnic Studies and Spanish at Willamette University. Michelle is passionate about political engagement, civil rights, and human rights and is committed to cultivating a more equitable Oregon.

Bio: Michelle Hicks is a Field Organizer at APANO. She was raised in San Jose, CA by her mother, a Korean immigrant, and two incredible older sisters. Her upbringing influenced her to study Politics with minors in American Ethnic Studies and Spanish at Willamette University. Michelle is passionate about political engagement, civil rights, and human rights and is committed to cultivating a more equitable Oregon.