Contributed by special guest writer, Elai Kobayashi-Solomon, in collaboration with APANO (see organization description at end of this blog)

My last name is the nightmare of substitute teachers. Kobayashi-Solomon. It doesn’t fit on the back of a soccer jersey, and it takes what feels like an eternity to scrawl out all 17 letters when I’m signing a document. There have been plenty of times when I’ve wished, for the sake of convenience, that I could delete the hyphen and simply call myself Elai Kobayashi or Elai Solomon.

Nevertheless, I am Elai Kobayashi-Solomon. And, as I’ve grown older, I’ve begun to realize that the seemingly innocuous hyphen which rests between the two halves of my last name is symbolic of my experiences as an Asian-American growing up in Chicago and attending college in Portland.

I was born in a small town just outside Tokyo to parents who had struggled to find a place to call home. My mother, who was born and raised in Japan, left her family behind and immigrated to the United States in search of bigger and better things when she was 23-years-old. My father, born in Houston, never felt comfortable in the conservative religious household in which he was raised, and he left the lone-star state for Tokyo in his mid-20s. They met in Japan, and, upon having me, decided to merge their last names into a single larger one which reflected their two distinct cultural identities: Kobayashi-Solomon.

My family moved to the United States when I was roughly three-years-old, and I spent the majority of my childhood and adolescence in a suburb of Chicago. Growing up, I constantly struggled to reconcile my Japanese and American identities, which often seemed completely separated by the hyphen that lay between them. On the one hand, raised in the United States, I attended public schools that were majority white, watched American television shows, and read about American news and politics. But on the other hand, I spoke Japanese with my mom, attended Japanese Saturday School, and was more comfortable eating with chopsticks than a fork and knife. I had the clear sense that I wasn’t completely American or completely Japanese, and there were times when I felt as though I was hopelessly caught between two cultures while never being entirely part of either.

My family moved to the United States when I was roughly three-years-old, and I spent the majority of my childhood and adolescence in a suburb of Chicago. Growing up, I constantly struggled to reconcile my Japanese and American identities, which often seemed completely separated by the hyphen that lay between them. On the one hand, raised in the United States, I attended public schools that were majority white, watched American television shows, and read about American news and politics. But on the other hand, I spoke Japanese with my mom, attended Japanese Saturday School, and was more comfortable eating with chopsticks than a fork and knife. I had the clear sense that I wasn’t completely American or completely Japanese, and there were times when I felt as though I was hopelessly caught between two cultures while never being entirely part of either.

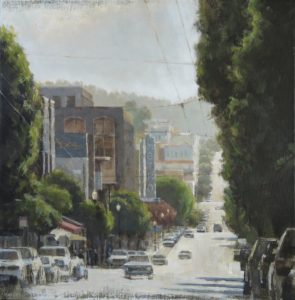

Recently, though, my outlook has changed. I’m not exactly sure why. Maybe it has to do with my trip to Japan a couple summers ago. Or maybe it was triggered by my new life as a college student in Portland, a city without much of a Japanese community, especially compared to that of the Chicagoland area. Walking through the bustling streets of downtown Tokyo in the summer of 2016, I felt simultaneously at home and alien. It had been several years since I had visited Japan, and I felt a deep, visceral attachment to both the city and the people who passed me on the streets. However, as I glanced at posters of celebrities I didn’t recognize and caught snippets of slang that I didn’t understand, I was also acutely aware that I was not too different from the hordes of tourists who arrive each year, marveling at unfamiliar cityscapes and cultural customs. My experiences in Portland have been in many ways similar. Without Japanese friends, acquaintances and family members to speak to, I could, if I wanted to, become Elai the American college student. However, before I even realized it, I felt myself being drawn towards elements of my Japanese background and heritage, whether it was via my work for APANO or the late-night ramen trips I sometimes make with friends.

Recently, though, my outlook has changed. I’m not exactly sure why. Maybe it has to do with my trip to Japan a couple summers ago. Or maybe it was triggered by my new life as a college student in Portland, a city without much of a Japanese community, especially compared to that of the Chicagoland area. Walking through the bustling streets of downtown Tokyo in the summer of 2016, I felt simultaneously at home and alien. It had been several years since I had visited Japan, and I felt a deep, visceral attachment to both the city and the people who passed me on the streets. However, as I glanced at posters of celebrities I didn’t recognize and caught snippets of slang that I didn’t understand, I was also acutely aware that I was not too different from the hordes of tourists who arrive each year, marveling at unfamiliar cityscapes and cultural customs. My experiences in Portland have been in many ways similar. Without Japanese friends, acquaintances and family members to speak to, I could, if I wanted to, become Elai the American college student. However, before I even realized it, I felt myself being drawn towards elements of my Japanese background and heritage, whether it was via my work for APANO or the late-night ramen trips I sometimes make with friends.

When I was in high school, these experiences may have led to feelings of isolation, confusion, and separation. But, thrust into a new environment with plenty of time to reflect, I realize that it needn’t be so. True, I may never feel totally at home walking into a Japanese konnbini or watching the Superbowl with friends. But, if I was simply Elai the American, I would have never had the opportunity to attain fluency in a foreign language, fly across the Pacific Ocean to stay with my obaachan, or learn kendo from a Japanese sword-fighting instructor. And if I was just Elai the Japanese, I wouldn’t be sitting here now attending a liberal arts college (non-existent in Japan) alongside many valued friends and peers. The hyphen sitting between “Kobayashi” and “Solomon” doesn’t have to be an impenetrable wall, forcing me into a binary choice between Japanese and American, neither of which I feel comfortable completely adopting. Rather, the hyphen is a bridge — an open connection that lets me combine and explore elements of both my Japanese and American identities, the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Author Bio: Elai is the Cultural Work & Placekeeping Intern at APANO. Born in Tokyo, Japan, Elai moved to the United States when he was three-years-old and was raised in Chicago, Illinois. Currently, Elai is an English major at Reed College. Through his internship at APANO, Elai hopes to learn more about nonprofit and social justice organizing, a field which he wishes to pursue in the future. In his free time, Elai enjoys reading, listening to podcasts, playing soccer, and writing for Reed’s student newspaper.

Author Bio: Elai is the Cultural Work & Placekeeping Intern at APANO. Born in Tokyo, Japan, Elai moved to the United States when he was three-years-old and was raised in Chicago, Illinois. Currently, Elai is an English major at Reed College. Through his internship at APANO, Elai hopes to learn more about nonprofit and social justice organizing, a field which he wishes to pursue in the future. In his free time, Elai enjoys reading, listening to podcasts, playing soccer, and writing for Reed’s student newspaper.

APANO: Established as a 501c3 nonprofit in 2010, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO) is a statewide, grassroots organization uniting Asians and Pacific Islanders to achieve social justice. They use their collective strengths to advance equity through empowering, organizing and advocating for communities. APANO’s strategic direction prioritizes four key focus areas: cultural work, leadership development, community organizing, and policy advocacy and civic engagement. Through APANO’s arts and cultural work, vibrant spaces are created where artists and communities can envision an equitable world through the tool of creative expression. APANO strives to impact beliefs, center the voices of those most impacted and silenced, and use arts and cultural work to foster unity and vitality within communities. Learn more about APANO on their website and read more writings by APANO members on Medium.

Oregon Literary Arts Announcement: Oregon Writers of Color Fellowship application deadline is July 9, 2018

The Writers of Color Fellowship is intended to fund writers of color to

initiate, develop, or complete a literary project in poetry, fiction,

literary nonfiction, drama, or young readers literature. One Writers of

Color Fellowship will be offered each year. All applications for the Writers

of Color Fellowship will also be considered for an Oregon Literary

Fellowship. Self-identified writers of color who are current, full-time

Oregon residents and who meet the eligibility requirements for Oregon

Literary Fellowships are eligible to apply. Full guidelines can be found at

http://www.literary-arts.org/what-we-do/oba-home/fellowships/fellowships/. Contact Susan Moore with questions, Susan@literary-arts.org, or 503-227-2583 ext 107.

Roberta May Wong is a conceptual/installation artist from Portland, Oregon. Recent exhibitions include: Friends of Lin Bo, a Three-Person Exhibit at Artist Repertory Theatre (2017); We the People, Group show at Blackfish Gallery (2017) and I-Ching Revolution: 101, an Installation at Indivisible (2016). Past exhibitions: Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center, Portland, OR; The Wing Luke Asian Museum’s touring exhibition “Beyond Talk: Redrawing Race” at The Wing Luke Asian Museum, South Seattle Community College of Art and Phinney Center Art Gallery (2005), Seattle, WA; Evergreen State College, WA; Portland Community College, Sylvania Campus, Portland, OR; Autzen Gallery, Portland State University, Portland, OR; New Zone Gallery, Eugene, OR; Hillsboro Cultural Center, Hillsboro, OR; and NW Artists’ Workshop, Portland, Oregon.

Roberta May Wong is a conceptual/installation artist from Portland, Oregon. Recent exhibitions include: Friends of Lin Bo, a Three-Person Exhibit at Artist Repertory Theatre (2017); We the People, Group show at Blackfish Gallery (2017) and I-Ching Revolution: 101, an Installation at Indivisible (2016). Past exhibitions: Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center, Portland, OR; The Wing Luke Asian Museum’s touring exhibition “Beyond Talk: Redrawing Race” at The Wing Luke Asian Museum, South Seattle Community College of Art and Phinney Center Art Gallery (2005), Seattle, WA; Evergreen State College, WA; Portland Community College, Sylvania Campus, Portland, OR; Autzen Gallery, Portland State University, Portland, OR; New Zone Gallery, Eugene, OR; Hillsboro Cultural Center, Hillsboro, OR; and NW Artists’ Workshop, Portland, Oregon.

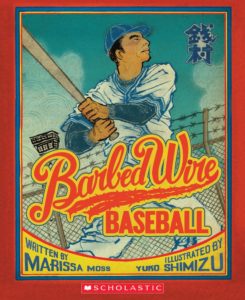

This past week, I read the book

This past week, I read the book  Bio: Anne Hawkins is a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco, California. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband and three children. Her happiest childhood memories are of time spent with her grandparents, and her favorite moments now are watching her own children build the same kinds of memories with their grandparents. She is always on the look-out for children’s books featuring Asian-American characters. Recommendations welcome: annehawk@yahoo.com.

Bio: Anne Hawkins is a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco, California. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband and three children. Her happiest childhood memories are of time spent with her grandparents, and her favorite moments now are watching her own children build the same kinds of memories with their grandparents. She is always on the look-out for children’s books featuring Asian-American characters. Recommendations welcome: annehawk@yahoo.com.

Bio: Robin Ye currently works a Field Organizer at the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO), helping to build political power for Asians and Pacific Islanders through policy advocacy and community organizing. He is Chinese-American and the only member of his entire family born in the United States. Robin grew up in Beaverton, Oregon, graduated from the International School of Beaverton before moving to Chicago to study Public Policy and Human Rights at the University of Chicago. He is also a proud member of the APAICS family (Asian Pacific American Institute for Congressional Studies).

Bio: Robin Ye currently works a Field Organizer at the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO), helping to build political power for Asians and Pacific Islanders through policy advocacy and community organizing. He is Chinese-American and the only member of his entire family born in the United States. Robin grew up in Beaverton, Oregon, graduated from the International School of Beaverton before moving to Chicago to study Public Policy and Human Rights at the University of Chicago. He is also a proud member of the APAICS family (Asian Pacific American Institute for Congressional Studies). How does one live in the world authentically? I tell people I’m an Oregonian, but in truth I was born in California. But I don’t remember any of that because we moved when I was a toddler to Ohio. At age 7, my family moved again to Connecticut and again at age 9 back to California and once more again to Oregon at age 12 in 2003. I’ve lived in Oregon since that time and because my ancestors are from Oregon having immigrated here from Japan in 1915, I usually say that I am from Oregon. But there were still times when I felt inauthentic. At Portland State University, I developed the habit of carrying an umbrella with me. My friends would tease, “Only Californians carry umbrellas.” So then, what does it mean to live authentically as an Oregonian? Or as a Japanese American? Or as an American? I’ve since come to take pride in my uniqueness as an umbrella-wielding youngster in Portland and with that pride I’ve discovered something else about identity. Living in the world authentically is not about foregoing umbrellas or passing litmus tests; living in the world authentically is about owning your identity by taking pride in exactly who you are.

How does one live in the world authentically? I tell people I’m an Oregonian, but in truth I was born in California. But I don’t remember any of that because we moved when I was a toddler to Ohio. At age 7, my family moved again to Connecticut and again at age 9 back to California and once more again to Oregon at age 12 in 2003. I’ve lived in Oregon since that time and because my ancestors are from Oregon having immigrated here from Japan in 1915, I usually say that I am from Oregon. But there were still times when I felt inauthentic. At Portland State University, I developed the habit of carrying an umbrella with me. My friends would tease, “Only Californians carry umbrellas.” So then, what does it mean to live authentically as an Oregonian? Or as a Japanese American? Or as an American? I’ve since come to take pride in my uniqueness as an umbrella-wielding youngster in Portland and with that pride I’ve discovered something else about identity. Living in the world authentically is not about foregoing umbrellas or passing litmus tests; living in the world authentically is about owning your identity by taking pride in exactly who you are.

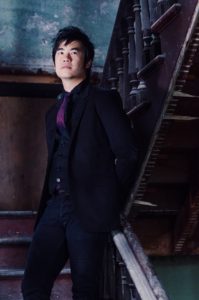

Contributed by Anthology author, Simon Tam

Contributed by Anthology author, Simon Tam

Bio: Simon Tam is an author, musician, entrepreneur, and activist. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. His work in the arts has been highlighted in over 3,000 media features across 200 countries including The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, BBC, NPR, TIME Magazine, and Rolling Stone.

Bio: Simon Tam is an author, musician, entrepreneur, and activist. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. His work in the arts has been highlighted in over 3,000 media features across 200 countries including The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, BBC, NPR, TIME Magazine, and Rolling Stone.

As an angst-filled teen, some of my more nascent theatrical attributes started to manifest. I became somewhat of a class clown and gained popularity, but I also loved performing music. I found creative outlets for myself in performance art despite my continued focus on academic success. Ultimately however, I felt discouraged because as much as a career in entertainment seemed like a pipe dream, it seemed like a pipe-dreamers pipe dream for an Asian American.

As an angst-filled teen, some of my more nascent theatrical attributes started to manifest. I became somewhat of a class clown and gained popularity, but I also loved performing music. I found creative outlets for myself in performance art despite my continued focus on academic success. Ultimately however, I felt discouraged because as much as a career in entertainment seemed like a pipe dream, it seemed like a pipe-dreamers pipe dream for an Asian American. Bio: Doug Kim studied economics at Duke University and was a former management consultant. He was also a professional poker player who, in 2006, managed to make it to the final table of the World Series of Poker Main Event in Las Vegas. Shortly after the financial crisis, he decided to pursue an acting career in Hollywood. He is now an executive producer, actor, and writer for a semi-autobiographical comedy series called

Bio: Doug Kim studied economics at Duke University and was a former management consultant. He was also a professional poker player who, in 2006, managed to make it to the final table of the World Series of Poker Main Event in Las Vegas. Shortly after the financial crisis, he decided to pursue an acting career in Hollywood. He is now an executive producer, actor, and writer for a semi-autobiographical comedy series called  Thoughts from Award-Winning Filmmaker, Myles Matsuno

Thoughts from Award-Winning Filmmaker, Myles Matsuno The Japanese Incarceration is something that’s glossed over in American history. It was brushed over in my high school and college educations. For some, it wasn’t taught at all. And I get it … it’s embarrassing. America didn’t save the day on this one. In fact, they dropped the ball. But you know what? So did I.

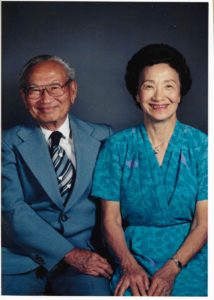

The Japanese Incarceration is something that’s glossed over in American history. It was brushed over in my high school and college educations. For some, it wasn’t taught at all. And I get it … it’s embarrassing. America didn’t save the day on this one. In fact, they dropped the ball. But you know what? So did I. I never took the time to really dig into what my grandparents and roughly 120,000 other Japanese Americans and immigrants went through in this country. It wasn’t until I was in my early twenties that I actually took the time to read the front page of the San Francisco Examiner that my father has framed and hanging on his wall. It’s the same enlarged one-sheet he’s had hanging on his wall for decades. The paper was published on December 8th 1941, and the title reads, “First S.F. Japanese Prisoner.” It has the picture of a Japanese man being handcuffed and escorted out of a hotel by the FBI. That prisoner was my great-grandfather, Ichiro Kataoka, and that hotel was his hotel. I learned that my family legacy is one that is touching, inspiring, and hopeful.

I never took the time to really dig into what my grandparents and roughly 120,000 other Japanese Americans and immigrants went through in this country. It wasn’t until I was in my early twenties that I actually took the time to read the front page of the San Francisco Examiner that my father has framed and hanging on his wall. It’s the same enlarged one-sheet he’s had hanging on his wall for decades. The paper was published on December 8th 1941, and the title reads, “First S.F. Japanese Prisoner.” It has the picture of a Japanese man being handcuffed and escorted out of a hotel by the FBI. That prisoner was my great-grandfather, Ichiro Kataoka, and that hotel was his hotel. I learned that my family legacy is one that is touching, inspiring, and hopeful. For years, this story resonated within me. I wanted to know everything about it. I would talk to my grandmother about what she went through. I would go to museum exhibits on the subject, read books, and Google whatever I could find online. I even filed for all the documents that were collected on Ichiro Kataoka during that time. And just like my father did with my sister and me, I wanted to document everything. I wanted something tangible. Something I could show my family for generations to come. So, without a real plan, I set out to do just that. Make a film based on my family’s experience of the Japanese Incarceration. And this process has forever changed my life.

For years, this story resonated within me. I wanted to know everything about it. I would talk to my grandmother about what she went through. I would go to museum exhibits on the subject, read books, and Google whatever I could find online. I even filed for all the documents that were collected on Ichiro Kataoka during that time. And just like my father did with my sister and me, I wanted to document everything. I wanted something tangible. Something I could show my family for generations to come. So, without a real plan, I set out to do just that. Make a film based on my family’s experience of the Japanese Incarceration. And this process has forever changed my life. First and foremost, I made this film for my family. I wanted to preserve our family’s history for current and future generations, so both my family and others will never forget what happened to real people in a time of war. Almost all of the footage in the film is personal. I digitized and captured four different generations dating all the way back to my great-grandfather. Releasing our family’s film to the public as a documentary does make us vulnerable, especially in an industry where critics can be harsh and rejection is common. Sometimes, I didn’t want to let the public see what happened to our family because this would open us up to the judgment of complete strangers. Would I do justice to my family’s story? Make my family proud?

First and foremost, I made this film for my family. I wanted to preserve our family’s history for current and future generations, so both my family and others will never forget what happened to real people in a time of war. Almost all of the footage in the film is personal. I digitized and captured four different generations dating all the way back to my great-grandfather. Releasing our family’s film to the public as a documentary does make us vulnerable, especially in an industry where critics can be harsh and rejection is common. Sometimes, I didn’t want to let the public see what happened to our family because this would open us up to the judgment of complete strangers. Would I do justice to my family’s story? Make my family proud? My hope for this film is that it not only educates the viewer but also brings them a sense of hope. A hope that good can come from even the darkest of situations. I don’t downplay Executive Order 9066 issued by President Roosevelt. It was a horrible time in our country. It was a time when racism led to fear and fear led to racism. But like my Aunt Toshi says in the film, “Well as bad as camp was, one thing, I met your dad here. … We were in block 11 they were in block 9 … If it wasn’t for camp you kids wouldn’t be here. … that’s the only good thing… .” That’s the message of hope I’m talking about and it’s overwhelming to see people recognize this hope after watching the film.

My hope for this film is that it not only educates the viewer but also brings them a sense of hope. A hope that good can come from even the darkest of situations. I don’t downplay Executive Order 9066 issued by President Roosevelt. It was a horrible time in our country. It was a time when racism led to fear and fear led to racism. But like my Aunt Toshi says in the film, “Well as bad as camp was, one thing, I met your dad here. … We were in block 11 they were in block 9 … If it wasn’t for camp you kids wouldn’t be here. … that’s the only good thing… .” That’s the message of hope I’m talking about and it’s overwhelming to see people recognize this hope after watching the film. As my grandma says in the legacy letter I found when making the film, “Just like my mother, I, too, have lived a life of shiawase.” Shi-a-wase in Japanese means fortunate or happiness.

As my grandma says in the legacy letter I found when making the film, “Just like my mother, I, too, have lived a life of shiawase.” Shi-a-wase in Japanese means fortunate or happiness. Bio: Born and raised in Los Angeles, CA, Myles Matsuno focuses on developing meaningful stories that convey strong messages through visual aesthetics. For him, everything he creates comes down to two final factors: the Audience and Moments. Having led efforts for ABC LA in the technical direction of shows such as The Academy Awards, Dancing with the Stars, NBA Finals, and more, Matsuno has also gained international recognition for his films because of their honest and inspiring messages. His films have been shown in many festivals and won awards throughout the country. His latest works are the feature, Christmas in July, and the documentary, First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family. His documentary is expected to be released in December 2017. Please check his websites:

Bio: Born and raised in Los Angeles, CA, Myles Matsuno focuses on developing meaningful stories that convey strong messages through visual aesthetics. For him, everything he creates comes down to two final factors: the Audience and Moments. Having led efforts for ABC LA in the technical direction of shows such as The Academy Awards, Dancing with the Stars, NBA Finals, and more, Matsuno has also gained international recognition for his films because of their honest and inspiring messages. His films have been shown in many festivals and won awards throughout the country. His latest works are the feature, Christmas in July, and the documentary, First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family. His documentary is expected to be released in December 2017. Please check his websites:  Among all the melancholic, endearing, funny photos was this dark piece of family history that would nag at me through the years. I had to know if my grandpa, who I barely remember since he passed away when I was three years old, was a criminal. You always want to believe that your country is fair and just and that the FBI would only go after the bad guys. My mom was a young girl of fourteen when the Japanese Imperial Air Force sent planes to destroy the US Naval Base in Honolulu at Pearl Harbor, so she had very little understanding of what was happening to her father, and eventually to her mother, herself and her five siblings. What she had to offer as an explanation was this: my grandfather was a businessman who was able to buy a hotel in the Japanese section of the city. In cornering that market, he would often drive out to the docks and greet incoming ships carrying passengers from Japan before the days of air travel. He would introduce himself as the owner of Aki Hotel and make them feel less like strangers in a strange land. It was partly an act of kindness, but it was mostly just smart. As a result of his frequent trips to the ships, bowing to greet new Japanese immigrants, along with his growing prominence in the Japanese community, he was secretly under surveillance.

Among all the melancholic, endearing, funny photos was this dark piece of family history that would nag at me through the years. I had to know if my grandpa, who I barely remember since he passed away when I was three years old, was a criminal. You always want to believe that your country is fair and just and that the FBI would only go after the bad guys. My mom was a young girl of fourteen when the Japanese Imperial Air Force sent planes to destroy the US Naval Base in Honolulu at Pearl Harbor, so she had very little understanding of what was happening to her father, and eventually to her mother, herself and her five siblings. What she had to offer as an explanation was this: my grandfather was a businessman who was able to buy a hotel in the Japanese section of the city. In cornering that market, he would often drive out to the docks and greet incoming ships carrying passengers from Japan before the days of air travel. He would introduce himself as the owner of Aki Hotel and make them feel less like strangers in a strange land. It was partly an act of kindness, but it was mostly just smart. As a result of his frequent trips to the ships, bowing to greet new Japanese immigrants, along with his growing prominence in the Japanese community, he was secretly under surveillance. What I do remember about my grandpa was that he was a small, quiet man. He couldn’t speak English well, so we had little actual conversation. It’s a typical Sansei dilemma. When the FBI cuffed him, he went peacefully to meet whatever fate his new country would impose on him. I’m sure he was scared and had no idea of the magnitude of what would follow for his family and 150,000 other people of Japanese ancestry trying to make America their new home. He was taken first as an example of what would happen to the entire Japanese community in San Francisco.

What I do remember about my grandpa was that he was a small, quiet man. He couldn’t speak English well, so we had little actual conversation. It’s a typical Sansei dilemma. When the FBI cuffed him, he went peacefully to meet whatever fate his new country would impose on him. I’m sure he was scared and had no idea of the magnitude of what would follow for his family and 150,000 other people of Japanese ancestry trying to make America their new home. He was taken first as an example of what would happen to the entire Japanese community in San Francisco. Flash forward to the early ‘70s. I had moved to Los Angeles to start a career in advertising. My grandfather had been long gone and the days of flipping through photo albums were far behind me. I kept in touch with my family as much as I could and would take frequent trips to San Francisco. On one of those trips, I heard that my cousin, Marjorie, had gotten a job at The Examiner. I didn’t connect the dots until a couple of years later that she might be able to access the microfilm of that newspaper article. I thought it would be great to send it to a color lab, make large framed posters and give them to my relatives on my mother’s side. Marjorie came through for me and in turn, I surprised my family with theatrical poster-sized sepia-toned framed copies. For me, the importance of that piece of family history was mostly personal, a piece of the Kataoka legacy.

Flash forward to the early ‘70s. I had moved to Los Angeles to start a career in advertising. My grandfather had been long gone and the days of flipping through photo albums were far behind me. I kept in touch with my family as much as I could and would take frequent trips to San Francisco. On one of those trips, I heard that my cousin, Marjorie, had gotten a job at The Examiner. I didn’t connect the dots until a couple of years later that she might be able to access the microfilm of that newspaper article. I thought it would be great to send it to a color lab, make large framed posters and give them to my relatives on my mother’s side. Marjorie came through for me and in turn, I surprised my family with theatrical poster-sized sepia-toned framed copies. For me, the importance of that piece of family history was mostly personal, a piece of the Kataoka legacy. Bio: Mark Matsuno was born and raised in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles at the age of twenty to pursue a career in advertising. After a three-year stint at Young & Rubicam West, he started his own graphic design boutique specializing in movie advertising. Currently, he has his own design firm in Glendale, CA. Much of his time is spent on high-profile films such as Jurassic World, Minions and many others. He is the proud father of son, Myles, and daughter, Alyssa.

Bio: Mark Matsuno was born and raised in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles at the age of twenty to pursue a career in advertising. After a three-year stint at Young & Rubicam West, he started his own graphic design boutique specializing in movie advertising. Currently, he has his own design firm in Glendale, CA. Much of his time is spent on high-profile films such as Jurassic World, Minions and many others. He is the proud father of son, Myles, and daughter, Alyssa. When a guy has had bad luck with women for awhile, he begins to think that he is jinxed. It seemed that every woman I met that I was attracted to was either involved with someone or didn’t like my style. My style back then was Hippie. Never a fashionable high point in the history of style, but I was making a statement about materialism and being a Hippie was part of the idealism that ran through the collegiate universe at that time. It was 1971 and I was living just off campus in a house that I shared with three other loosely associated friends who were like-minded. We all wore our hair long and liked flannel shirts and blue jeans. That year, I wore the same flannel shirt and jeans every day and a lot of my friends would wear the same “outfit” most of the time. I could recognize my friends from a great distance just from their clothing. The comfort of cotton was more important than being fashionable. The more you washed flannel the softer it became. I really loved my blue, white and red plaid shirt. I would wash it once a week and I was good. After a year of wearing it and washing it, the fabric had lost some of its bulk and the colors had slowly washed out so it was getting thin. So thin was it that one of my roommates had put his finger into a small hole and ripped it in half. I went down to JC Penney’s and bought two new flannel shirts the same day.

When a guy has had bad luck with women for awhile, he begins to think that he is jinxed. It seemed that every woman I met that I was attracted to was either involved with someone or didn’t like my style. My style back then was Hippie. Never a fashionable high point in the history of style, but I was making a statement about materialism and being a Hippie was part of the idealism that ran through the collegiate universe at that time. It was 1971 and I was living just off campus in a house that I shared with three other loosely associated friends who were like-minded. We all wore our hair long and liked flannel shirts and blue jeans. That year, I wore the same flannel shirt and jeans every day and a lot of my friends would wear the same “outfit” most of the time. I could recognize my friends from a great distance just from their clothing. The comfort of cotton was more important than being fashionable. The more you washed flannel the softer it became. I really loved my blue, white and red plaid shirt. I would wash it once a week and I was good. After a year of wearing it and washing it, the fabric had lost some of its bulk and the colors had slowly washed out so it was getting thin. So thin was it that one of my roommates had put his finger into a small hole and ripped it in half. I went down to JC Penney’s and bought two new flannel shirts the same day.