Contributed by special guest writer, Brian Liu, as part of our collaboration with APANO (see organization description at end of this blog)

When David Chang, in his scathingly honest Netflix cooking show, Ugly Delicious, asked a group of Asian chefs and food writers if, as kids, they wanted to be white, I didn’t expect to see everyone around the table raise their hands. I grew up in Honolulu, Hawaii, where Asians outnumber everyone, with Whites coming in a close second, and the native population limping behind all the other races with its permanently broken ankle. Growing up, all my close friends were Asian. But looking back, we already knew that the world didn’t belong to people who looked like us. At least not the world that seemed to matter, the world of beautiful thin white folk who were the heroes and champions in our imaginations and televisions. It was also around that time that my best friend, who is Japanese, started saying that he hated Japanese people. Jokingly, of course.

When David Chang, in his scathingly honest Netflix cooking show, Ugly Delicious, asked a group of Asian chefs and food writers if, as kids, they wanted to be white, I didn’t expect to see everyone around the table raise their hands. I grew up in Honolulu, Hawaii, where Asians outnumber everyone, with Whites coming in a close second, and the native population limping behind all the other races with its permanently broken ankle. Growing up, all my close friends were Asian. But looking back, we already knew that the world didn’t belong to people who looked like us. At least not the world that seemed to matter, the world of beautiful thin white folk who were the heroes and champions in our imaginations and televisions. It was also around that time that my best friend, who is Japanese, started saying that he hated Japanese people. Jokingly, of course.

Grilled pork salad with thick rice noodles at Nam Giao.

In an episode of Ugly Delicious, Chang recounts how being a first-generation Asian American means existing nowhere. In the States, he is seen as a Korean first, even though he grew up in Virginia. And despite all the Korean food he’s cooked and eaten as a kid, he doesn’t speak the language and is treated like an American when he travels to Korea. He claims that his cooking is a byproduct of his alienation. I had to admit, watching David talk about his experiences around being Asian American, that being in the majority in Hawaii sheltered me from the constellating, reclaiming language that other minorities sometimes share. Instead we formed local identities, modeled ourselves after a culture handed down by the mixed-plate meals of plantation workers. Some of us who had inherited the tongues of our parents absorbed the culture our parents left behind, becoming more Asian than American. Most of us ended-up half-there half-not, our English a mix of mannerisms and slurs we had learned at the dinner table, school, the mall, the beach. The same friend who made anti-Japanese jokes commented on his frustration at barbershops. “All the haircuts in the books they have there are worn by these handsome white men,” I remember him saying. “It’s not gonna look the same on me. I’m fat. And Japanese.”

Many Chinese immigrants post-1960’s came from wealthy, educated, and cultured backgrounds. Hawaii is a perfect example of this. Other Asian families can trace their lineage back to plantation workers who toiled alongside other Pacific Islanders in the sugar industry. Then there are those like me, born in America, who have parents like mine. Parents who are well-intentioned and are — in the upward-mobile American-economic-striving sense — white.

Our complicity in the ongoing struggle between White and Black America is often understated. And so is the position we occupy. Think of Elaine Chao, wife of Senator Mitch McConnell, who recently defended her husband, famous for his obstructionist partisan polemics, from immigration protesters, saying of both McConnell and the President, “I stand by my man … both of them.” Chao is an immigrant from Taiwan. So are both of my parents.

Ugly Delicious is a portrait of our complicated American palettes, our messy lurching histories and the colliding intersections that create and destroy new flavors, new intimacies, and new forms of intolerance. In the rice episode, Chang interviews a Chinese chef whose menu caters to the Americanized Chinese palette: General Tso’s chicken, beef and broccoli. Chang asks the man, “This isn’t what you grew up eating. Why do you cook food you don’t eat for people who don’t look like you?” The man doesn’t miss a beat. “ … If Chinese people come in and want me to cook something that isn’t on the menu, I’ll cook it. But this is what White people want to eat. So that’s why it’s on the menu.”

Ugly Delicious is a portrait of our complicated American palettes, our messy lurching histories and the colliding intersections that create and destroy new flavors, new intimacies, and new forms of intolerance. In the rice episode, Chang interviews a Chinese chef whose menu caters to the Americanized Chinese palette: General Tso’s chicken, beef and broccoli. Chang asks the man, “This isn’t what you grew up eating. Why do you cook food you don’t eat for people who don’t look like you?” The man doesn’t miss a beat. “ … If Chinese people come in and want me to cook something that isn’t on the menu, I’ll cook it. But this is what White people want to eat. So that’s why it’s on the menu.”

In another episode, David Chang learns how to make dumplings from an elderly woman who reminds me much of my grandmother. I hated dumplings when I was young. But now, I remember the affection that accompanied the food. I remember my grandmother’s concern when I pushed the plate away. I wanted hamburgers not dumplings. And yet she would always push the plate back in front of me. “Please eat,” she would say, “I know you’re hungry.”

Shows like Ugly Delicious have me asking myself about where I speak from when I try to speak about race. It has me thinking about what it means to participate politically as an Asian American, to claim that identity for myself, to claim a right to that community and history, in a time where Race Politics and Immigration Policy continue to offer up disenfranchised minorities and communities of color as scapegoats for our collective problems. It has me wondering about the well-being of friends who might be asking questions about their gender identities and trying to cope with the pressures they face from their parents and the culture their parents come from.

Shows like Ugly Delicious have me asking myself about where I speak from when I try to speak about race. It has me thinking about what it means to participate politically as an Asian American, to claim that identity for myself, to claim a right to that community and history, in a time where Race Politics and Immigration Policy continue to offer up disenfranchised minorities and communities of color as scapegoats for our collective problems. It has me wondering about the well-being of friends who might be asking questions about their gender identities and trying to cope with the pressures they face from their parents and the culture their parents come from.

I am a student of Hanif Abdurraqib when he writes, “Even now, I’m not as invested in things getting better as I am in things getting honest.” The truth is that a lot of us have excused ourselves from the table, from the work of honesty, especially when it involves deciding “to be honest about not loving the spaces we have claimed as our own.” Hanif asks, “Who is going to be brave enough to ask where home is and seek out something else if they don’t like the answer?”

Asian American stories range wildly and it is sometimes hard to separate the lies from the truth. When I first heard the term pathological liar, I didn’t think it applied to me. But the lie does not just conceal the reality that being Asian American is not the same as being White American. The lie is that some of us grew up treated as if we are white, grew up wanting to be white with all the privileges that whiteness confers, yet know, deep down, we never can be.

The lie that I have been telling myself is that I can live without asking what it means to be Asian American. The lie that I have been telling myself is that I am full when I am not. I am hungry. My grandmother would be happy to hear it. She would tell me the dumplings are ready.

Bio: Brian is one of APANO’s 2019 Vote Fellows. He was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii and is a first-generation Asian American, the son of two Taiwanese immigrants. He graduated from The Evergreen State College in 2016 with a Bachelors in Liberal Arts. His degree placed an emphasis on Institutional Sociology and the History of Technology. His undergraduate research involved studying ways new technologies displace traditional forms of living. He currently attends the Oregon Institute for Creative Research.

Bio: Brian is one of APANO’s 2019 Vote Fellows. He was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii and is a first-generation Asian American, the son of two Taiwanese immigrants. He graduated from The Evergreen State College in 2016 with a Bachelors in Liberal Arts. His degree placed an emphasis on Institutional Sociology and the History of Technology. His undergraduate research involved studying ways new technologies displace traditional forms of living. He currently attends the Oregon Institute for Creative Research.

Brian’s political engagement work in Oregon started with Forward Together during the 2018 Election season where he worked as a canvasser for Reproductive and Immigration Justice. His work as a canvasser invoked his passion for civic engagement and direct action as models for participating in local forms of social justice and policy change. He hopes to continue working in and on behalf of his community, learning more about the problems that the AAPI community faces, and participating in political work grounded in grassroot and intersectional philosophy. In his spare time, he loves eating and reading whatever he can get his hands on.

APANO: Established as a 501c3 nonprofit in 2010, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO) is a statewide, grassroots organization uniting Asians and Pacific Islanders to achieve social justice. We use our collective strengths to advance equity through empowering, organizing and advocating with our communities. APANO’s strategic direction prioritizes four key focus areas: cultural work, leadership development, community organizing, and policy advocacy and civic engagement. Through APANO’s arts and cultural work, we create a vibrant space where artists and communities can envision an equitable world through the tool of creative expression. We strive to impact beliefs, center the voices of those most impacted and silenced, and use arts and cultural work to foster unity and vitality within our communities. Learn more about APANO on our website and read more writings by APANO members on Medium.

Bio: Lynn Yarne is an artist and educator from Portland, Oregon. She works within animation and collage to address generational narratives and histories. She is curious about community, participatory works, magic, and rejuvenation. Lynn holds a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MAT from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She currently makes art projects for and about the public education system.

Bio: Lynn Yarne is an artist and educator from Portland, Oregon. She works within animation and collage to address generational narratives and histories. She is curious about community, participatory works, magic, and rejuvenation. Lynn holds a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MAT from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She currently makes art projects for and about the public education system. My work included in Descendent Threads is rooted in a reverent response to the mysteries that were always part of having a lovely Chinese mom. Watching her use her elegant and enigmatic tool for counting inspired wonderment. For ABACUS, I cast seemingly countless grains of rice into oversized bead forms. But instead of aligning on a rod, they are arranged like a blossom that rests upon a coiling velvet cushion.

My work included in Descendent Threads is rooted in a reverent response to the mysteries that were always part of having a lovely Chinese mom. Watching her use her elegant and enigmatic tool for counting inspired wonderment. For ABACUS, I cast seemingly countless grains of rice into oversized bead forms. But instead of aligning on a rod, they are arranged like a blossom that rests upon a coiling velvet cushion. My mom spoke a language I could not understand, but in which she seemed her most buoyant while speaking. In making TRANSLATION, I have taken apart a Chinese-English dictionary. Using a pattern she taught me as a child, I’ve folded each page into a small boat. These 400 boats follow each other in a double spiral, out and in, across hand-drawn lines.

My mom spoke a language I could not understand, but in which she seemed her most buoyant while speaking. In making TRANSLATION, I have taken apart a Chinese-English dictionary. Using a pattern she taught me as a child, I’ve folded each page into a small boat. These 400 boats follow each other in a double spiral, out and in, across hand-drawn lines. These red lines are the battens of a sail, latitude/longitude lines, or the lines on the pages of a calligraphy practice book.

These red lines are the battens of a sail, latitude/longitude lines, or the lines on the pages of a calligraphy practice book. In the surfaces of my FAN SUITE paintings I see the influence of my mother’s Chinese “dreamstones.” As a child I was transfixed by these thin slices of stone, mounted in carved hardwood frames and revealing inclusions and veining that resembled landscape.

In the surfaces of my FAN SUITE paintings I see the influence of my mother’s Chinese “dreamstones.” As a child I was transfixed by these thin slices of stone, mounted in carved hardwood frames and revealing inclusions and veining that resembled landscape. I am fortunate to have with me now, many treasures my mom was able to bring with her to America, and that I grew up with, including her fans. The shapes I use in the on-going painting series I call FAN SUITE are based on 17th, 18th and 19th century Chinese fans. There is the tradition of these fans to depict flora and landscape, suggesting that their restorative breeze could transport us to these lovely fresh scented locations.

I am fortunate to have with me now, many treasures my mom was able to bring with her to America, and that I grew up with, including her fans. The shapes I use in the on-going painting series I call FAN SUITE are based on 17th, 18th and 19th century Chinese fans. There is the tradition of these fans to depict flora and landscape, suggesting that their restorative breeze could transport us to these lovely fresh scented locations. My great-grandfather was Rev Chan Hon Fan. As a young man he was a missionary working with the Chinese Methodist Episcopal Society along the Pacific Coast from Puget Sound to the San Francisco Bay Area,1870-1900. The Oregon Historical Society has documented a letter written by him and published in the Oregonian in 1886. It was printed in his exact words, and titled

My great-grandfather was Rev Chan Hon Fan. As a young man he was a missionary working with the Chinese Methodist Episcopal Society along the Pacific Coast from Puget Sound to the San Francisco Bay Area,1870-1900. The Oregon Historical Society has documented a letter written by him and published in the Oregonian in 1886. It was printed in his exact words, and titled

BIO: Ellen George attended Austin College, Sherman, Texas, and the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, Ireland. She has lived in Washington State over twenty-five years. Ellen has received residencies at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, Otis, Oregon, and c3:initiative, Portland, Oregon. Her work is included in numerous collections including Portland Art Museum, Tacoma Art Museum, 4Culture and King County, Seattle Public Art, The Nines Hotel Atrium, Portland, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer.

BIO: Ellen George attended Austin College, Sherman, Texas, and the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, Ireland. She has lived in Washington State over twenty-five years. Ellen has received residencies at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, Otis, Oregon, and c3:initiative, Portland, Oregon. Her work is included in numerous collections including Portland Art Museum, Tacoma Art Museum, 4Culture and King County, Seattle Public Art, The Nines Hotel Atrium, Portland, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Ellen is represented by

Ellen is represented by

BIO: Born and raised in Portland, OR, Roberta Wong grew up working behind the counter and in the back kitchen of her family’s grocery and restaurant, Tuck Lung, in Portland’s Chinatown. She attended Portland State University, graduating in Sculpture in 1983. Chinatown was a part of her daily life until 1985 when she entered the nonprofit art sector as a gallery director and art administrator. She spent the next two decades promoting diversity in the arts and creating opportunities for artists-of-color.

BIO: Born and raised in Portland, OR, Roberta Wong grew up working behind the counter and in the back kitchen of her family’s grocery and restaurant, Tuck Lung, in Portland’s Chinatown. She attended Portland State University, graduating in Sculpture in 1983. Chinatown was a part of her daily life until 1985 when she entered the nonprofit art sector as a gallery director and art administrator. She spent the next two decades promoting diversity in the arts and creating opportunities for artists-of-color.

Contributed by special guest writer, Marleen Wallingford

Contributed by special guest writer, Marleen Wallingford In 2017,

In 2017,  On November 15, 2018, a special ceremony was held at the school to dedicate a chestnut tree donated by the Sato Family and a soon-to-be-constructed historical plaque. The chestnut tree is significant to the Sato family. On their farm, there was a chestnut tree whose fruit was used as a special addition to meals. Chestnuts were very special to Mrs. Sato who used them in special treats. The tree and the farm are only a memory now but if you go to Sato Elementary, the plaque there will tell the Satos’ story.

On November 15, 2018, a special ceremony was held at the school to dedicate a chestnut tree donated by the Sato Family and a soon-to-be-constructed historical plaque. The chestnut tree is significant to the Sato family. On their farm, there was a chestnut tree whose fruit was used as a special addition to meals. Chestnuts were very special to Mrs. Sato who used them in special treats. The tree and the farm are only a memory now but if you go to Sato Elementary, the plaque there will tell the Satos’ story. Contributed by special guest writer, Anne Hawkins

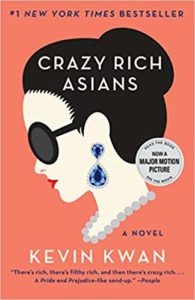

Contributed by special guest writer, Anne Hawkins So, imagine my surprise, when I picked up Kevin Kwan’s highly acclaimed novel

So, imagine my surprise, when I picked up Kevin Kwan’s highly acclaimed novel  Bio: Anne Hawkins is a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco, California. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband and three children. Until Kevin Kwan comes out with his next novel, she is on the lookout for other happily-ever-after novels featuring Asian and Asian-American characters. Recommendations welcome:

Bio: Anne Hawkins is a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco, California. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband and three children. Until Kevin Kwan comes out with his next novel, she is on the lookout for other happily-ever-after novels featuring Asian and Asian-American characters. Recommendations welcome:  While growing up on Guam, I never really took the time to think about what my race and ethnicity meant to me. I was very comfortable because I identified as Chamorro, part of the majority race on Guam. Wherever I went, I felt like I belonged and could connect easily to others around me.

While growing up on Guam, I never really took the time to think about what my race and ethnicity meant to me. I was very comfortable because I identified as Chamorro, part of the majority race on Guam. Wherever I went, I felt like I belonged and could connect easily to others around me. Some people praise my English. Some ask if I had worn “real” clothes before and just generally question whether my island is a “civilized” community. On top of the assumptions that people have about islander communities, I am also really bothered when people assume I am a member of the Latinx, Asian, or Native American communities and treat me in ways that reflect their assumptions of those groups as well. A common assumption that others have of me is that I am a Latinx man, which is either said explicitly or when they greet me in Spanish. I am often faced with the discomfort of navigating out of those situations, especially when I realize I am being engaged because they think I’m of that other race.

Some people praise my English. Some ask if I had worn “real” clothes before and just generally question whether my island is a “civilized” community. On top of the assumptions that people have about islander communities, I am also really bothered when people assume I am a member of the Latinx, Asian, or Native American communities and treat me in ways that reflect their assumptions of those groups as well. A common assumption that others have of me is that I am a Latinx man, which is either said explicitly or when they greet me in Spanish. I am often faced with the discomfort of navigating out of those situations, especially when I realize I am being engaged because they think I’m of that other race. BIO: Brandon Cruz is a member of the field team at APANO, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon. Born and raised on the island of Guam, Brandon came to Portland to complete a degree in social work and psychology at the University of Portland. He identifies as a native Chamorro and is interested in creating systemic changes, mental health, and the relations between territories and the US. During his free time, Brandon enjoys playing guitar, hiking, spending time with friends, and exploring the food scene in Portland.

BIO: Brandon Cruz is a member of the field team at APANO, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon. Born and raised on the island of Guam, Brandon came to Portland to complete a degree in social work and psychology at the University of Portland. He identifies as a native Chamorro and is interested in creating systemic changes, mental health, and the relations between territories and the US. During his free time, Brandon enjoys playing guitar, hiking, spending time with friends, and exploring the food scene in Portland. One summer, I had the privilege of observing U.S. Naturalization ceremonies as part of my work with the

One summer, I had the privilege of observing U.S. Naturalization ceremonies as part of my work with the  For those in the ceremony, to what set of responsibilities, histories, and privileges did these New Americans just swear an oath of allegiance? As I sat there nervously clapping, did it pain other Americans as much as it did me that these immigrants were pledging support to a government that does not want them? I’m sure the immigrants were aware of this complicated dilemma – is there not something inherently progressive and accepting about immigrants who leave behind their lives and culture to adopt new ones in the U.S.? Are immigrants not the most accepting and understanding people of other peoples and cultures, the most realistic and sober-minded when it comes to the challenges and hardships that accompany dreams of a better life?

For those in the ceremony, to what set of responsibilities, histories, and privileges did these New Americans just swear an oath of allegiance? As I sat there nervously clapping, did it pain other Americans as much as it did me that these immigrants were pledging support to a government that does not want them? I’m sure the immigrants were aware of this complicated dilemma – is there not something inherently progressive and accepting about immigrants who leave behind their lives and culture to adopt new ones in the U.S.? Are immigrants not the most accepting and understanding people of other peoples and cultures, the most realistic and sober-minded when it comes to the challenges and hardships that accompany dreams of a better life? Robin Ye is the Lead Political Organizer at APANO (Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon). He is Chinese-American and the only member of his entire family born in the United States. Robin grew up in Beaverton, Oregon and attended high school at the International School of Beaverton.

Robin Ye is the Lead Political Organizer at APANO (Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon). He is Chinese-American and the only member of his entire family born in the United States. Robin grew up in Beaverton, Oregon and attended high school at the International School of Beaverton. I remember celebrating Chinese New Year. While my friends didn’t celebrate it, my family made it special. Dennis, my dad, came home early from work, and my godparents, Anne and Donald, drove down from Vancouver. Kristy, my mom, laid out a red tablecloth on top of Grandma’s oval, claw-foot oak table, a 100-year-old heirloom. On this day, our house transformed. Mom hung crimson paper bearing Chinese characters laced in gold, which colored a formerly empty wall. Knot ornaments, the traditional bell, and a paper dragon coiled the dining room curtain rod. The entryway smelled of incense. We ate red barbeque pork slices with hot mustard, stir-fry chicken, red bean paste buns, yakisoba noodles with cashews and red bell peppers. The next day it was over. Where the red had been, now lay a white lace tablecloth. Mom sat at the table, reading Wilson’s 100 Cupboards. Beneath her feet, down in the garage, Dad tinkered underneath his 1930s Ford hot rod. Channel 8 played in the background as I ate my favorite TV dinner, chicken alfredo and garlic bread. With fork and knife in hand, this was home. Because chopsticks never felt right between my fingers. We only used them once a year and then tucked them away in a kitchen drawer, buried underneath plastic forks and knives, oven mitts and hot mats. And I never knew what the Chinese characters meant either. They would appear for one day a year and then disappear into a box.

I remember celebrating Chinese New Year. While my friends didn’t celebrate it, my family made it special. Dennis, my dad, came home early from work, and my godparents, Anne and Donald, drove down from Vancouver. Kristy, my mom, laid out a red tablecloth on top of Grandma’s oval, claw-foot oak table, a 100-year-old heirloom. On this day, our house transformed. Mom hung crimson paper bearing Chinese characters laced in gold, which colored a formerly empty wall. Knot ornaments, the traditional bell, and a paper dragon coiled the dining room curtain rod. The entryway smelled of incense. We ate red barbeque pork slices with hot mustard, stir-fry chicken, red bean paste buns, yakisoba noodles with cashews and red bell peppers. The next day it was over. Where the red had been, now lay a white lace tablecloth. Mom sat at the table, reading Wilson’s 100 Cupboards. Beneath her feet, down in the garage, Dad tinkered underneath his 1930s Ford hot rod. Channel 8 played in the background as I ate my favorite TV dinner, chicken alfredo and garlic bread. With fork and knife in hand, this was home. Because chopsticks never felt right between my fingers. We only used them once a year and then tucked them away in a kitchen drawer, buried underneath plastic forks and knives, oven mitts and hot mats. And I never knew what the Chinese characters meant either. They would appear for one day a year and then disappear into a box. My name is Ivy and I was born in Fuzhou, Jiangxi, China. I don’t know who I am or where I came from – and I wasn’t left a note. The orphanage gave me the name “Fu-HuiHong.” When Mom came to get me, I was being raised by an old Chinese woman in a humble room. And I cried when she took me away. At seven-months-old, I was whisked away to America and lived in Beaverton, Oregon for the next 18 years. When I talk about my identity, I say it in a roundabout way because I don’t even know how to explain it to myself. When I look in the mirror for too long, I get confused and dismayed. I remember high school, the questions about who I am or what I am and the constant pressure to give an answer. And I give one. It satisfies people, while I feel reduced. How do I explain what it means to be me? How do I describe what it feels like to look in the mirror and not even register my face as Chinese? How do I tell people that I feel foreign to myself at times? I have so much more to say and so much more to give.

My name is Ivy and I was born in Fuzhou, Jiangxi, China. I don’t know who I am or where I came from – and I wasn’t left a note. The orphanage gave me the name “Fu-HuiHong.” When Mom came to get me, I was being raised by an old Chinese woman in a humble room. And I cried when she took me away. At seven-months-old, I was whisked away to America and lived in Beaverton, Oregon for the next 18 years. When I talk about my identity, I say it in a roundabout way because I don’t even know how to explain it to myself. When I look in the mirror for too long, I get confused and dismayed. I remember high school, the questions about who I am or what I am and the constant pressure to give an answer. And I give one. It satisfies people, while I feel reduced. How do I explain what it means to be me? How do I describe what it feels like to look in the mirror and not even register my face as Chinese? How do I tell people that I feel foreign to myself at times? I have so much more to say and so much more to give. Bio: Ivy is a member of the Field Team of APANO, Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon. She recently graduated from Willamette University with a bachelor’s degree in politics, history, and a minor in American ethnic studies (AES). During her time at Willamette, she was a library student manager, the university archives intern, a mentor to first year students, and a Sexual Assault Response Ally (SARA) on her campus. She also interned for State Representative Susan McLain and later became her legislative assistant for the 2018 session. For her theses, Ivy wrote about her passions for social justice by highlighting Chinese exclusion in Oregon and the politics of the #MeToo movement. She hopes to continue work in non-profit, helping to promote social justice, civic engagement, and empowerment. She currently volunteers at the Center for Hope and Safety in Salem, Oregon.

Bio: Ivy is a member of the Field Team of APANO, Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon. She recently graduated from Willamette University with a bachelor’s degree in politics, history, and a minor in American ethnic studies (AES). During her time at Willamette, she was a library student manager, the university archives intern, a mentor to first year students, and a Sexual Assault Response Ally (SARA) on her campus. She also interned for State Representative Susan McLain and later became her legislative assistant for the 2018 session. For her theses, Ivy wrote about her passions for social justice by highlighting Chinese exclusion in Oregon and the politics of the #MeToo movement. She hopes to continue work in non-profit, helping to promote social justice, civic engagement, and empowerment. She currently volunteers at the Center for Hope and Safety in Salem, Oregon. Bio: Ava Kamb is a member of the field team at APANO, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon. Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, she spent most of her life in the California Bay Area before coming up to Portland to complete a degree in religion at Reed College. She is mixed-race and has always been interested in multifaceted identities and the blurring of boundaries. In her free time, she enjoys watching documentaries, traveling, and exploring Portland and the Pacific Northwest.

Bio: Ava Kamb is a member of the field team at APANO, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon. Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, she spent most of her life in the California Bay Area before coming up to Portland to complete a degree in religion at Reed College. She is mixed-race and has always been interested in multifaceted identities and the blurring of boundaries. In her free time, she enjoys watching documentaries, traveling, and exploring Portland and the Pacific Northwest.