Contributed by special guest author/editor Shawn Wong

Shawn Wong is the author of two novels, Homebase and American Knees, and editor or co-editor of six anthologies of Asian American or American multicultural literature. He is a professor of English and Cinema & Media Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. His website is: ShawnWongWrites.com

Shawn Wong is the author of two novels, Homebase and American Knees, and editor or co-editor of six anthologies of Asian American or American multicultural literature. He is a professor of English and Cinema & Media Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. His website is: ShawnWongWrites.com

Last summer I waged a social media war against Penguin Classics for what I believed to be their piracy of John Okada’s No-No Boy, trampling on a valid copyright by claiming that the book was in the public domain because I filled out the copyright form incorrectly when the co-editors of Aiiieeeee!, Jeffery Chan, Frank Chin, Lawson Inada, and I, used our own money to republish the novel in 1976 as a CARP publication (Combined Asian-America Resources Project). In addition, the original publication by Charles Tuttle Co. was in 1957, which meant that both copyrights were still in force. Later, in 1979, I transferred the rights to the University of Washington Press. Penguin Classics had made no attempt to contact the Okada family or the UW Press prior to releasing their edition. They were essentially, in my opinion, making a stand on commerce over decency.

During my public campaign against Penguin Classics and its Vice-President and Publisher, Elda Rotor, many people and organizations joined in the battle, supporting my stand. Some of the first to stand with me were Viet Thanh Nguyen, David Henry Hwang, Asian American professors and teachers, and independent bookstores from all over the country who returned copies of the Penguin edition, refusing to sell it. That support, combined with the mainstream media picking up on the “David vs. Goliath” story and the work of intellectual property attorneys, actually brought the battle to a quick end. The teamwork was textbook Asian American activism at its best. The only difference between the activism of 50 years ago and now is the power of social media. I should know, I was there at the beginning.

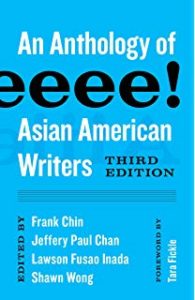

My co-editors and I discovered Okada’s novel 50 years ago in a used bookstore for 50 cents and following the publication of Aiiieeeee! in 1974, we made it our mission to bring No-No Boy and other canonical works of Asian America back into print. Many literary scholars have critiqued our anthology over the years and pointed out its failings or its tone or its dated definition of Asia America (we even included in the new edition of the anthology a foreward by Tara Fickle in which she documents that criticism), but many did not realize that the anthology was the production of activism more than literary scholarship. The book made a stand that Asian American literature deserved a seat at the table of American Literature. We often pushed back against the publishing companies and editors who rejected our manuscript with often demeaning and dismissive letters of rejection. It was no surprise when the only publisher to find us a legitimate literary voice was Howard University Press.

My co-editors and I discovered Okada’s novel 50 years ago in a used bookstore for 50 cents and following the publication of Aiiieeeee! in 1974, we made it our mission to bring No-No Boy and other canonical works of Asian America back into print. Many literary scholars have critiqued our anthology over the years and pointed out its failings or its tone or its dated definition of Asia America (we even included in the new edition of the anthology a foreward by Tara Fickle in which she documents that criticism), but many did not realize that the anthology was the production of activism more than literary scholarship. The book made a stand that Asian American literature deserved a seat at the table of American Literature. We often pushed back against the publishing companies and editors who rejected our manuscript with often demeaning and dismissive letters of rejection. It was no surprise when the only publisher to find us a legitimate literary voice was Howard University Press.

We never met John Okada before he died in 1971, but we vowed that his achievement be recognized and that his place in American literature be secure. What Penguin Classics didn’t realize when they went to market, is that the publishing history of the novel and the people behind it were as important as the book, which is why the UW Press edition of the novel contains three supporting essays about the literary history.

Under the pressure of all of this social media activism, Penguin Classics chose to withdraw their edition of No-No Boy from all distribution in the US in an arrangement with the UW Press and only distribute their version abroad. They also agreed to pay the Okada family and estate royalties for all copies sold—something they avoided when they released their version of the novel. The UW Press version of the novel continues to be published as it has been for the last 40 years here in the US and worldwide. The current sales of the UW Press is 160,000 copies sold. That number combined with the CARP sales of 6,000 copies far exceeds the original Tuttle printing of 1500 copies.

This last January, I found out that Elda Rotor was attending the Modern Language Association conference in Seattle at the same time the UW Press was doing a book launch for the new edition of Aiiieeeee! on the occasion of its 45th anniversary. The agreement between Penguin Classics and the UW Press and the Okada family had been signed. I invited Elda to come to the book launch and she agreed. When we shook hands, I told her that I supported her efforts to publish Asian American literature and offered my advice should she ever need it. I didn’t enter into the campaign against Penguin Classics to shame them or disgrace them. I’m a teacher and I thought there was a lesson in the history of Okada’s book that everyone should know.

This last January, I found out that Elda Rotor was attending the Modern Language Association conference in Seattle at the same time the UW Press was doing a book launch for the new edition of Aiiieeeee! on the occasion of its 45th anniversary. The agreement between Penguin Classics and the UW Press and the Okada family had been signed. I invited Elda to come to the book launch and she agreed. When we shook hands, I told her that I supported her efforts to publish Asian American literature and offered my advice should she ever need it. I didn’t enter into the campaign against Penguin Classics to shame them or disgrace them. I’m a teacher and I thought there was a lesson in the history of Okada’s book that everyone should know.

There’s no monetary incentive for me to defend No-No Boy and its publishing history or an author I never met, rather I’m defending my own history with the book and my voice in urging people to read this novel I found in a used bookstore when I was an unpublished undergraduate student trying to be a writer myself.

To buy copies of No-No Boy, click here. For Aiiieeeee, click here.

At 87 years old, there are few things my paternal grandmother does not have an opinion on; fewer still that she is not ready to share. From skirt lengths to savings bonds, rest assured that Bobbie has something to say about that. One topic spared from commentary from my no-nonsense grandma? Her four-year stint in an internment camp as a young teen (photo to left is Bobbie at age 12-13 at Heart Mt, WY).

At 87 years old, there are few things my paternal grandmother does not have an opinion on; fewer still that she is not ready to share. From skirt lengths to savings bonds, rest assured that Bobbie has something to say about that. One topic spared from commentary from my no-nonsense grandma? Her four-year stint in an internment camp as a young teen (photo to left is Bobbie at age 12-13 at Heart Mt, WY). Her reluctance to speak about her adolescence made it all the more romantic to me. I envisioned shiny saddle shoes, first kisses over chocolate malts, and glass bottle sodas with nickel movies. The reality, I later learned, was not necessarily devoid of those Americana stereotypes, but warped through the lens of shame and fear, behind barbed wire fences and guard towers.

Her reluctance to speak about her adolescence made it all the more romantic to me. I envisioned shiny saddle shoes, first kisses over chocolate malts, and glass bottle sodas with nickel movies. The reality, I later learned, was not necessarily devoid of those Americana stereotypes, but warped through the lens of shame and fear, behind barbed wire fences and guard towers. Lauren Yanase is a recent graduate of St. Mary’s Academy in Portland, Oregon. An avid storyteller, Lauren has previously written creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of Japanese American internment and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her

Lauren Yanase is a recent graduate of St. Mary’s Academy in Portland, Oregon. An avid storyteller, Lauren has previously written creative fiction and nonfiction accounts of Japanese American internment and has been recognized regionally and nationally for her writing. In 2019, she earned the Girl Scout Gold Award for her  Bobbie Shirota features as Yanase’s protagonist and narrator, recalling her family’s story of forced relocation in 1942 to their return to Los Angeles almost a decade later.

Bobbie Shirota features as Yanase’s protagonist and narrator, recalling her family’s story of forced relocation in 1942 to their return to Los Angeles almost a decade later.  An upcoming play will be performed by the Oregon Children’s Theatre at the Winningstad Theatre in Portland, OR in late February and March. “

An upcoming play will be performed by the Oregon Children’s Theatre at the Winningstad Theatre in Portland, OR in late February and March. “ David Mura has written two memoirs,

David Mura has written two memoirs,  Jeff, Frank and Lawson were all older than me by 8 to 12 years. I was still in college. By the time I graduated in 1971, we had the manuscript to Aiiieeeee! in our hands. We had found 14 writers to put in the anthology that my professors said did not exist. You might say that I majored in Asian American literature except there were no classes, no teachers, no grades, not even independent study credit. My side gig was Asian American literature while I was still writing papers on Spenser and Shakespeare and Yeats. I ended up teaching myself the subject that I would eventually teach in my first job as a college professor in 1972 at Mills College. I entered graduate school in Creative Writing at San Francisco State College in 1971 and I shopped our manuscript around to publishers without success. We often got back insulting and ignorant comments or questions such as inquiring whether or not the stories in the anthology were in translation or that the “least ethnic pieces were the best” or that the stories were interesting as social history rather than literature.

Jeff, Frank and Lawson were all older than me by 8 to 12 years. I was still in college. By the time I graduated in 1971, we had the manuscript to Aiiieeeee! in our hands. We had found 14 writers to put in the anthology that my professors said did not exist. You might say that I majored in Asian American literature except there were no classes, no teachers, no grades, not even independent study credit. My side gig was Asian American literature while I was still writing papers on Spenser and Shakespeare and Yeats. I ended up teaching myself the subject that I would eventually teach in my first job as a college professor in 1972 at Mills College. I entered graduate school in Creative Writing at San Francisco State College in 1971 and I shopped our manuscript around to publishers without success. We often got back insulting and ignorant comments or questions such as inquiring whether or not the stories in the anthology were in translation or that the “least ethnic pieces were the best” or that the stories were interesting as social history rather than literature. In retrospect, it’s not surprising to note that African American presses were the first to recognize the legitimacy of Asian American literature. My first three books were published by African American presses. Our anthology was reviewed everywhere from the Rolling Stone to The New Yorker to The New York Times with rave reviews. We received only two bad reviews—both from the only Asian American reviewers to review the anthology—one in Bridge Magazine and the other in the Honolulu Advertiser. One reviewer took exception to the fact that we stated there was Asian American literary English specific to the author’s ethnicity, a kind of street English, and the other reviewer noted all the Asian people we had not included even though he could not name the names of the excluded writers.

In retrospect, it’s not surprising to note that African American presses were the first to recognize the legitimacy of Asian American literature. My first three books were published by African American presses. Our anthology was reviewed everywhere from the Rolling Stone to The New Yorker to The New York Times with rave reviews. We received only two bad reviews—both from the only Asian American reviewers to review the anthology—one in Bridge Magazine and the other in the Honolulu Advertiser. One reviewer took exception to the fact that we stated there was Asian American literary English specific to the author’s ethnicity, a kind of street English, and the other reviewer noted all the Asian people we had not included even though he could not name the names of the excluded writers. The University of Washington Press has published the third edition of

The University of Washington Press has published the third edition of  David Mura has written two memoirs,

David Mura has written two memoirs,  BIO:

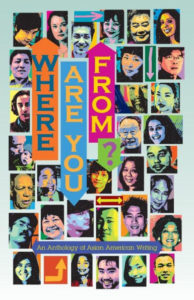

BIO:  When our Asian American activist group put together the anthology, Where Are You From?, we decided that the question we are often asked would make a good title for our book because it expressed many of our experiences as AAs in America. The question can be interpreted in many ways, depending on who is asking and how they are asking the question. It can be interested. Wary. Looking for reasons to accept or reject. Befriend or report to the authorities. The question might make us feel like The Other, as not belonging even though many of us are American citizens. Sometimes we choose to believe that the question is asked as a chance to explain ourselves. Sometimes we walk away from the question feeling resentful that we are obligated to prove that, even though we aren’t White, we still have a right to be in the United States, too.

When our Asian American activist group put together the anthology, Where Are You From?, we decided that the question we are often asked would make a good title for our book because it expressed many of our experiences as AAs in America. The question can be interpreted in many ways, depending on who is asking and how they are asking the question. It can be interested. Wary. Looking for reasons to accept or reject. Befriend or report to the authorities. The question might make us feel like The Other, as not belonging even though many of us are American citizens. Sometimes we choose to believe that the question is asked as a chance to explain ourselves. Sometimes we walk away from the question feeling resentful that we are obligated to prove that, even though we aren’t White, we still have a right to be in the United States, too. When we move to another place, it’s never without a lot of anxiety and difficulties… but I have a feeling that most people move because they want better lives and are willing to risk everything. That is why my grandparents moved to Hawaii from Japan. That is why my husband and I moved to Oregon from Hawaii. Is that such a bad motivation? Isn’t that how progress is made? By people wanting better lives for themselves and their children?

When we move to another place, it’s never without a lot of anxiety and difficulties… but I have a feeling that most people move because they want better lives and are willing to risk everything. That is why my grandparents moved to Hawaii from Japan. That is why my husband and I moved to Oregon from Hawaii. Is that such a bad motivation? Isn’t that how progress is made? By people wanting better lives for themselves and their children? Valerie Katagiri is co-editor of Where Are You From: An Anthology of Asian American Writing and coordinates the web-blogs for the book’s related AsianAmericanWriting.com website. She would love to hear your stories.

Valerie Katagiri is co-editor of Where Are You From: An Anthology of Asian American Writing and coordinates the web-blogs for the book’s related AsianAmericanWriting.com website. She would love to hear your stories. Correcting my mother’s emails and work announcements almost every day was tiring. She called me every day at all hours, saying that her request was very important and I should not let her down. Everyone will see her communication, so it is best not to mess up. Growing up, I was always annoyed with her because this responsibility fell to me, a 10-year-old. I saw how people treated her, felt how inconvenient it was for me to incessantly proofread every single document she produced, and was angry that I was the translator of important documents. Moreover, I saw how she got passed over for promotion countless times because of my failures to translate well enough. I just did not understand why she did not just try harder to improve her English and do it herself.

Correcting my mother’s emails and work announcements almost every day was tiring. She called me every day at all hours, saying that her request was very important and I should not let her down. Everyone will see her communication, so it is best not to mess up. Growing up, I was always annoyed with her because this responsibility fell to me, a 10-year-old. I saw how people treated her, felt how inconvenient it was for me to incessantly proofread every single document she produced, and was angry that I was the translator of important documents. Moreover, I saw how she got passed over for promotion countless times because of my failures to translate well enough. I just did not understand why she did not just try harder to improve her English and do it herself. Bio: Michelle Hicks is the Census Intern at APANO. She is originally from San Jose, CA, and is Korean American. She is a senior at Willamette University and upon graduation will receive a Bachelors of Arts in Politics with minors in American Ethnic Studies and Spanish. Michelle is passionate about political engagement, civil rights, and human rights and hopes to cultivate a more equitable Oregon.

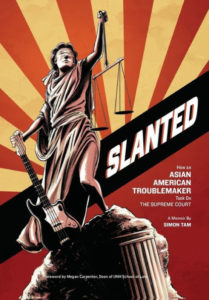

Bio: Michelle Hicks is the Census Intern at APANO. She is originally from San Jose, CA, and is Korean American. She is a senior at Willamette University and upon graduation will receive a Bachelors of Arts in Politics with minors in American Ethnic Studies and Spanish. Michelle is passionate about political engagement, civil rights, and human rights and hopes to cultivate a more equitable Oregon. I can’t believe that it’s been a couple of months since my memoir, Slanted: How an Asian American Troublemaker Took on the Supreme Court, was released. Since then, I’ve been traveling across the country presenting this story and engaging in thoughtful conversations with activists throughout the country. This has been especially meaningful because it’s been providing me with an opportunity to share the

I can’t believe that it’s been a couple of months since my memoir, Slanted: How an Asian American Troublemaker Took on the Supreme Court, was released. Since then, I’ve been traveling across the country presenting this story and engaging in thoughtful conversations with activists throughout the country. This has been especially meaningful because it’s been providing me with an opportunity to share the BIO: Simon Tam is an author, musician, activist, and troublemaker. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. He is the founder of The Slants Foundation, an organization dedicated to providing scholarships and mentorship to artist-activists of color.

BIO: Simon Tam is an author, musician, activist, and troublemaker. He is best known as the founder and bassist of The Slants, the world’s first and only all-Asian American dance rock band. He is the founder of The Slants Foundation, an organization dedicated to providing scholarships and mentorship to artist-activists of color. I am from a small gold-mining town in Northern California called Grass Valley. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are 12,860 residents of Grass Valley; 188 identify as Asian and 11,493 identify as white. My mother and I are two of those 188. We are also two of only three in my family who live in the United States. The year I graduated from high school, there was one other Asian American enrolled in my school of 784 students. I was the only student who was Chinese American. Growing up, I fixated upon these numbers, feeling the pressure of these statistics weighing on me. I would think to myself over and over again, “My actions are responsible for 50% of the Asian American representation here.” I felt that whatever I did would define who Chinese Americans were in this community. These numbers surrounded me like the bars of a cage, a constant reminder of my cultural isolation.

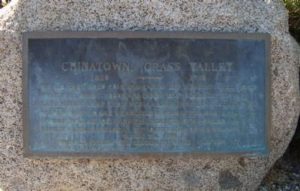

I am from a small gold-mining town in Northern California called Grass Valley. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are 12,860 residents of Grass Valley; 188 identify as Asian and 11,493 identify as white. My mother and I are two of those 188. We are also two of only three in my family who live in the United States. The year I graduated from high school, there was one other Asian American enrolled in my school of 784 students. I was the only student who was Chinese American. Growing up, I fixated upon these numbers, feeling the pressure of these statistics weighing on me. I would think to myself over and over again, “My actions are responsible for 50% of the Asian American representation here.” I felt that whatever I did would define who Chinese Americans were in this community. These numbers surrounded me like the bars of a cage, a constant reminder of my cultural isolation. I kept reading and eventually learned that the majority of Chinese residents in Grass Valley had either died, left after economic prospects dried up, or were driven out of town by angry, white mobs. All that was left is a small plaque commemorating the site were this Grass Valley Chinatown had once stood. To this day, I’ve never been able to find that plaque. But now, whenever I go home, I no longer feel so imprisoned by my Chineseness among this white majority. When I walk around, I can feel the spirits of the Chinese Americans who came before me. I can feel the memory of their footsteps on the paths I take. I know that though I never met them, and that I never will, I hold their legacy within me. I carry the torch of the Grass Valley Chinatown that once was. Though in this moment I may be one of only 188 Asian Americans, I am also one of thousands that ever were. And when I remember that, I don’t feel so alone.

I kept reading and eventually learned that the majority of Chinese residents in Grass Valley had either died, left after economic prospects dried up, or were driven out of town by angry, white mobs. All that was left is a small plaque commemorating the site were this Grass Valley Chinatown had once stood. To this day, I’ve never been able to find that plaque. But now, whenever I go home, I no longer feel so imprisoned by my Chineseness among this white majority. When I walk around, I can feel the spirits of the Chinese Americans who came before me. I can feel the memory of their footsteps on the paths I take. I know that though I never met them, and that I never will, I hold their legacy within me. I carry the torch of the Grass Valley Chinatown that once was. Though in this moment I may be one of only 188 Asian Americans, I am also one of thousands that ever were. And when I remember that, I don’t feel so alone. Bio: Margie was born and raised in Northern California and is a mixed-race second-generation Chinese American. She graduated from Reed College in 2018 with a degree in history. Her senior thesis focused on Chinese American cuisine and how restaurant owners created a sense of authenticity in their establishments during the Cold War. In Fall 2019 Margie will be starting a PhD program in Asian American History. In her free time she enjoys cooking and eating at local restaurants, reading, and spending time with her tiny dog, Chicken Combo.

Bio: Margie was born and raised in Northern California and is a mixed-race second-generation Chinese American. She graduated from Reed College in 2018 with a degree in history. Her senior thesis focused on Chinese American cuisine and how restaurant owners created a sense of authenticity in their establishments during the Cold War. In Fall 2019 Margie will be starting a PhD program in Asian American History. In her free time she enjoys cooking and eating at local restaurants, reading, and spending time with her tiny dog, Chicken Combo.